The research received support from several institutions, including the Royal College of Surgeons, the Academy of Medical Sciences, Health Education England, the National Institute for Health Research, and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

A team from the University of Cambridge has developed a flexible electronic device that wraps around the spinal cord. This device could change the treatment of spinal injuries, which often result in severe disability and paralysis. The device was created by engineers, neuroscientists, and surgeons. It records and stimulates nerve signals between the brain and spinal cord, significantly improving existing methods.

Current treatments involve high-risk surgeries with electrodes piercing the spinal cord or brain implants. The new Cambridge device provides a safer alternative. It is capable of 360-degree recording and captures a complete picture of spinal cord activity without invasive procedures. The findings were published in Science Advances.

Professor George Malliaras, a research co-leader from the Department of Engineering, explained that the spinal cord carries nerve impulses to and from the brain. Damage to the spinal cord interrupts this traffic, causing severe disability, including loss of sensory and motor functions. Dr Damiano Barone from the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, also a co-leader, noted that most technologies for monitoring or stimulating the spinal cord only interact with motor neurons along the dorsal part of the spinal cord, providing an incomplete picture.

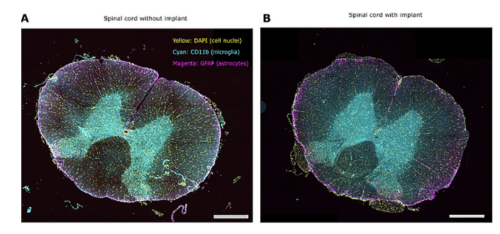

Inspired by microelectronics, the team created biocompatible devices a few millionths of a meter thick using advanced photolithography and thin film deposition techniques. These high-resolution implants wrap around the spinal cord, intercepting and recording signals on the axons or nerve fibres without causing damage. They noted the challenges in creating spinal implants this way but highlighted recent advances in engineering and neurosurgery that facilitated this progress. In tests on live animal and human cadaver models, the devices demonstrated their ability to stimulate limb movement and bypass complete spinal cord injuries, showing very low latency.

The team explained that adding brain surgery on top of spinal surgery increases patient risk. Still, this new device collects all necessary information from the spinal cord in a less invasive way, making it a safer approach for treating spinal injuries. While treatments using these devices are still several years away, they could soon be valuable for monitoring spinal cord activity during surgery, leading to improved treatments for conditions like chronic pain, inflammation, and hypertension.