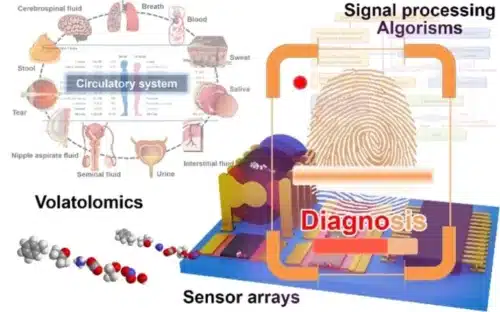

Credit: Nano Research, Tsinghua University Press

Scientists at the Nano Research department at Tsinghua University are working on a robot nose that could sniff out chemical compounds from breath, sweat, tears and other bodily emissions and might be considered fingerprints of thousands of diseases. But to take this concept—known as ‘volatolomics’—and its associated diagnostic technologies from the laboratory through to commercialisation will require collaboration across many disciplines.

An exhaustive new review of this nascent field aims to be a bridge between the many disparate actors involved. When you inhale a perfume, encounter the scent of flowers or spices, or suffer through a gust of pollutants, what your body senses are volatile organic compounds, chemicals that have a low boiling point and thus evaporate quickly. That is, they are volatile, and these chemicals as a group are called Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs).

All organisms consciously release VOCs for various purposes including defence, communication and reproduction. VOCs are also released incidentally as part of biological processes, including illnesses. Those VOCs released are also distinctive to each of these processes. This means that there is a particular VOC signature or fingerprint associated with a disease. Such VOCs related to the disease are released long before people are aware that anything is wrong with them, and thus also long before any doctor can carry out a diagnostic technique, whether via blood tests, X-rays, tissue samples or any other evaluation or lab test. Additionally, the bonus is the reduction of any invasive procedure from such diagnosis via a ‘sniffing robot’ which means that it would be painless as well, unlike many existing diagnostic techniques.

“But the field is so young, and draws in researchers from many fields such as chemistry, electrical engineering, computer science, materials science, and of course clinicians who deal with patients every day, who are unused to speaking to each other, who typically employ different methodologies, and who often do not even use the same terms,” said Yun Qian, a co-author of the review and researcher with the Cancer Center of Zhejiang University.

“So we brought a bunch of us from these various disciplines together to write a comprehensive review paper that we hope will work as a bridge connecting each other’s expertise in this sprawling field.”

“This part of the review was crucial, as such a list of targets has been highly sought after by the chemists, materials scientists, and electrical engineers in particular,” added Mingshui Yao, another of the authors and researcher at the State Key Laboratory of Multi-phase Complex Systems with the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

“They needed to know what the fingerprints or ‘biomarkers’ are that they are designing their diagnostic equipment for. Now they can just look this up.”

The team hopes that with the review as a reference point for everyone involved, these voids can be filled and technology development obstacles overcome, especially involving better VOC absorbing materials, sensing materials, sensor structures, and data-processing methods.