Materials scientists Nicole Kleger and Simona Fehlmann have developed a 3D printing process for producing salt templates to build complex objects with small pore sizes that could have a wide range of applications

Many researchers are finding ways to obtain biodegradable bone implants for restoring normal bone functions. This would avoid the need for a second surgery for bone material. Therefore, scientists have developed a 3D printing process to print a framework out of salt, which they further filled with liquid magnesium. Once the lightweight metal is cooled and hardened, the researchers leach out the salt framework, this results in an object made of highly porous magnesium that would be suitable, for example, as a biodegradable bone implant

“If one loses a tooth, the jawbone underneath disintegrates very quickly,” Kleger explains. Before a dental implant can be inserted, the bone must first be rebuilt. Currently, surgeons need bone material from the hip that acts as a second surgical site. Therefore, they could opt for customized bone implants made of magnesium alloys, into which bone-forming cells can migrate and which will degrade over time. Kleger and Fehlmann could implement their process to obtain precisely this type of implant.

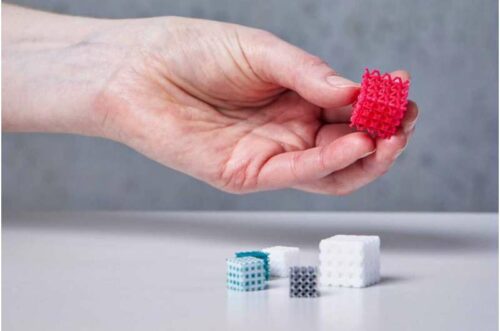

The journal Advanced Materials reported that researchers together with an interdisciplinary team, have improved and modified their previous process to create more complex salt scaffolds with even finer pores. The researchers led by Kleger and Fehlmann used a stereolithography device and ink based on salt particles rather than using an extrusion-based printer that prints out thin filaments of salt paste in a grid-like pattern from a fine nozzle

Mixing the ink with suitable monomers makes it light-sensitive. This enables the monomers to combine and form hard polymers once exposed to light which will help in building complex structures layer by layer. The salt framework created in this way then serves as a mold, or a negative template, to be filled with another material.

In the next step of this novel process, the materials scientists then filled the prefabricated structures with magnesium and aluminum, and plastic, or wrapped them with carbon composite material instead. Their new technique lets the researchers produce much more complex objects and reduces pore size from 0.5 millimeters to 0.1 millimeters.

This research produces three-dimensional scaffolds for cell cultures and it can be useful in space travel as “On space missions, weight is money,” Kleger says. The lightweight metal components fabricated with their process would be ideal for use in spaceships or rockets.

Click here for the Published Research Paper