Researchers at the University of Missouri have implemented artificial intelligence to conduct anatomical research without the need for dissection of animals

Previously, scientists had to use scalpels, scissors, and even their own hands to conduct anatomical research and to understand muscle and organ functioning. Holliday, an associate professor of pathology and anatomical sciences also recalls the moment when the t. rex’s giant skull being transported into Boeing’s Santa Susana Field Laboratory in California to be imaged in one of the aerospace company’s massive CAT scanners normally used to scan jet engines on commercial airplanes. Hence, Holliday and his colleagues are using artificial intelligence to see inside an animal or a person, down to a single muscle fiber without even need for a cut. AI can train computer programs to locate a muscle fiber in an image, similar to a CAT scan. Further, researchers will use the data to develop detailed 3-D computer models of muscles to analyze how they work together in the body for motor control.

“The digitization process is not only useful to our lab and research,” Lessner said, a recent MU alumna . “It makes our work shareable with other researchers to help hasten scientific advancement, and we can also share them with the public as educational and conservation tools. Specifically, my work looking at the soft tissues and bony correlates in these animals has not only created hundreds of future questions to answer but also revealed many unknowns. In that way, not only did I gain imaging skills to help with my future work, but I now have more than a career-worth of avenues to explore.”

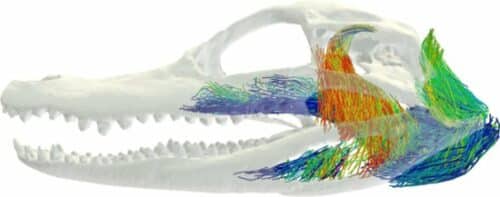

Holliday, along with some of his current and former students, were undergoing research to study the bite force of a crocodile. The 3-D models of muscle architecture will assist the team to understand how the muscle is oriented in crocodile heads to help increase their bite force. Several years ago, Holliday’s lab initially started its experiments with 3-D imaging. This study showed the development of a 3-D model of the skeletal muscles in a European starling. Contrast imaging data and machine learning approaches can now model the 3D architecture of jaw musculature.

“Jaw muscles have long been studied in mammals with the assumption that relatively simple descriptors of muscle anatomy can tell you a great deal about skull function,” Sellers said, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago. “This study shows how complex jaw muscle anatomy is in a reptile group.” Holliday envisions taking their 3-D anatomical models a step further by studying how human hands have evolved from their evolutionary ancestors.

“With better knowledge of actual muscle anatomy, we can figure out how the T. rex could do fine motor controls, and more nuanced behaviors, such as bite force and feeding behavior,” Holliday said.

Click here for the Published Research Paper