Organ-on-a-Chip technology has the potential to mimic complicated body illnesses by simulating various organ functions on a chip. Researchers from Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering have employed microchip manufacturing technologies to develop microfluidic culture devices that imitate the intricate shapes and functioning of human organs – including the liver, kidney, and brain tissues.

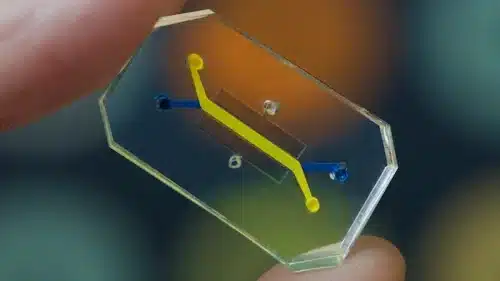

The goal is to reduce animal testing and speed up drug development. The microdevices are typically made of a clear, flexible polymer with microfluidic channels lined with human organ and blood vascular cells. These channels range in size from 10 to 100 micrometres in diameter, but they have a vast surface area and high mass transfer, allowing the observer to see how medications affect them.

Sensing mechanisms are an integral part of OoCs. The study uses biosensors for monitoring models with metabolic activities, barrier functions, and electromechanical properties. Electrical activities in the nervous system can be measured using biosensors. Because neurons grow in a densely packed, highly ordered, and 3D environment, multi-electrode arrays (MEAs) are useful in such instances.

To investigate the operation of the immune system, researchers at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute cultivated human B- and T-cells inside a microfluidic OoC, also known as an LF (lymphoid follicle) chip. The researchers claim that these chips can also predict the response to various vaccines.

“Animals have been the gold-standard research models for developing and testing new vaccines, but their immune systems differ significantly from our own and do not accurately predict how humans will respond to them. Our LF Chip offers a way to model the complex choreography of human immune responses to infection and vaccination, and could significantly speed up the pace and quality of vaccine creation in the future,” said first author Girija Goyal, PhD and a Senior Staff Scientist at the Wyss Institute.