A relationship between tunable electrical and magnetic properties in a 2D semiconductor has been discovered by Columbia University chemists and physicists, with possible applications in spintronics, quantum computing, and fundamental research.

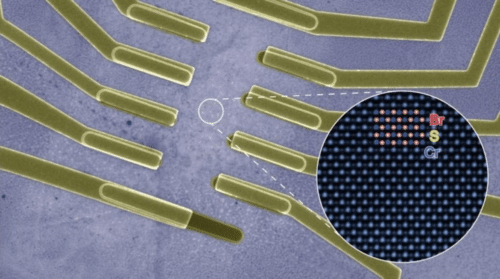

In a substance called chromium sulphide bromide, a team of chemists and physicists from Columbia University discovers a strong relationship between electron transport and magnetism (CrSBr). “CrSBr is infinitely easier to work with than other 2D magnets, which lets us fabricate novel devices and test their properties,” said Evan Telford, a postdoc in the Roy lab who graduated with a PhD in physics from Columbia in 2020.

“CrSBr is infinitely easier to work with than other 2D magnets, which lets us fabricate novel devices and test their properties,” said Evan Telford, a postdoc in the Roy lab who graduated with a PhD in physics from Columbia in 2020. The researchers studied CrSBr layers using an electric field at various electron densities, magnetic fields, and temperatures—variable characteristics that can be altered to induce diverse effects in a material. CrSBr’s magnetic altered as its electrical characteristics changed.

“Semiconductors have tunable electronic properties. Magnets have tunable spin configurations. In CrSBr, these two knobs are combined,” said Roy. “That makes CrSBr attractive for both fundamental research and for potential spintronics application.”

According to Telford, magnetism is a difficult feature to measure directly, especially as the size of the material reduces, but measuring how electrons travel with a metric termed resistance is simple. Resistance in CrSBr can be used as a surrogate for magnetic states that are otherwise unobservable. “That’s incredibly powerful,” Roy added, particularly as researchers attempt to make circuits out of 2D magnets in the future, which may be utilised for quantum computing and storing huge quantities of data in a small space.

The link between the material’s electronic and magnetic properties was due to defects in the layers—for the team, a lucky break, said Telford. “People usually want the ‘cleanest’ material possible. Our crystals had defects, but without those, we wouldn’t have observed this coupling,” he said.