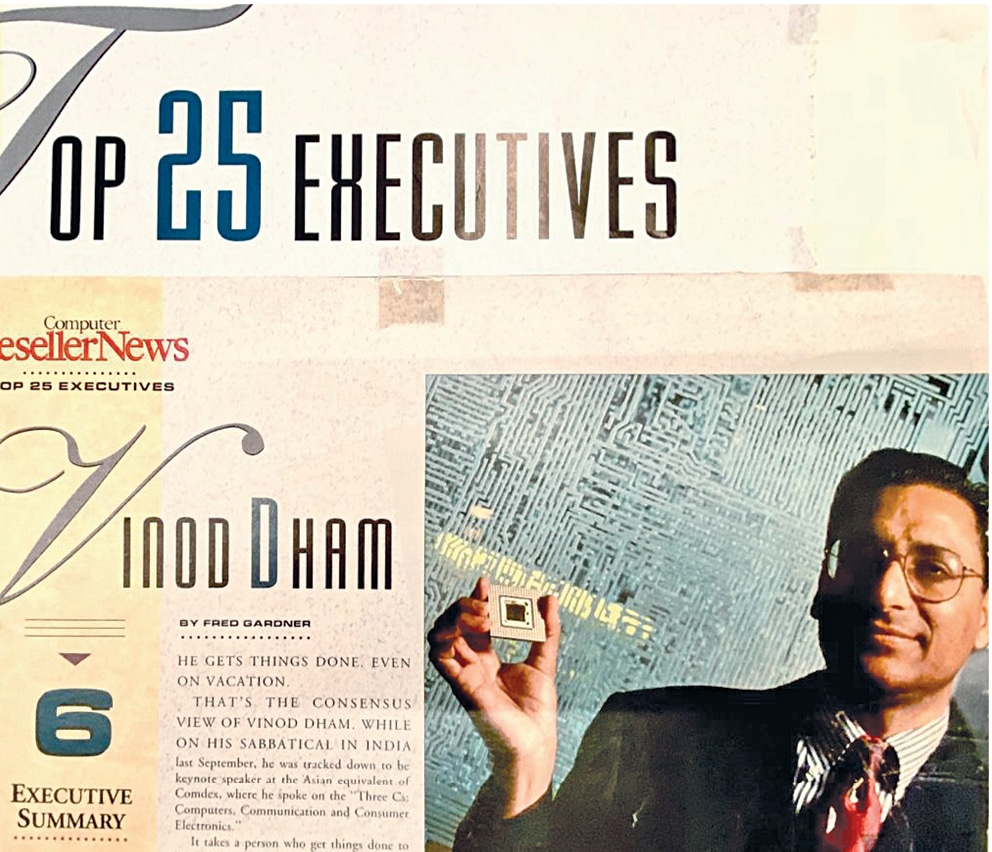

Hailing from a middle-class, partition-affected family, reaching the USA only with eight dollars in his pocket, building a multi-billion dollar business as the ‘Father of the Pentium Chips,’ Vinod Dham—an Indian-American engineer, entrepreneur, and venture capitalist—continues his fearless journey. In a conversation with Sudeshna Das, consulting editor at EFY, he shares the story of his life.

Born in Pune, Maharashtra, Vinod Dham comes from a partition-affected, middle-class family. His parents shifted to India with three sons and one daughter from Rawalpindi, now in Pakistan, to escape the post-partition crisis. Vinod was the fourth son, who was born in free India, in 1950.

Vinod’s father was a civilian in the Army, in-charge of the supply chains, such as spare parts for army equipment. His mother was a homemaker.

Vinod’s siblings were also well established in their professional life. His eldest brother did his MBA and was a banker in Delhi. He retired as GM at Union Bank of India. His second eldest brother was a physician and retired as Air Marshal in the Indian Air Force. He also served as the dean of the Armed Forces Medical College, Pune. Vinod’s third brother was an accountant and his sister had a master’s degree.

Vinod mentions his mother as a big inspiration. He explains how supportive his mother was in encouraging him to higher study in the USA even after the death of his father. Vinod recalls asking her, “Do you want me to go?” She replied without blinking, “You must go. It is your destiny. It will ‘make’ you. I will manage. Don’t worry about me.” It was a powerful message for Vinod. “She could have stopped me and I would have stopped in a second, but she did not,” he explains.

| “My mother was the biggest hero in the whole family in my mind. She was the glue that kept the family together, nurturing, loving, confidence-building, believed in faith and therefore taught us that and some great values that have come in handy all my life. When I look back and try to pick a person who has inspired my life, it invariably comes down to my mom.” |

| —Vinod Dham |

Looking back at the early years

Vinod recalls himself as a “quite a fearless person” since his school days. His school was far away from home, and he used to take a train to go to school along with his sister. He would invariably try to step into the train while it had already started moving. He vividly remembers how fellow passengers saved him once when he was almost going to fall through the tracks. Perhaps, that is an indication of his risk-taking nature. The same nature led him to explore and reach new heights in life, be it in the form of moving to a new country with eight dollars in his pocket or taking the risk of leading some huge projects.

While describing his school days, Vinod recalls, “Not only was I fearless, but also pretty outgoing and extrovert. I had the reputation of a troublemaker. I got into trouble quite a few times with the principal—even for things I had not done. Once, somebody had put some black coal tar on some spots on a statue. It was a horrific thing and the entire school was shocked. I was not involved in that activity, but somebody mentioned my name as the offender. I could not convince my teachers about my innocence, so I was forced to apologise in front of the whole school for something which was done by someone else. I had to even convince my sister, who was a student of the same school, about my innocence. This incident left a deep scar on my mind.”

This awful experience helped Vinod learn something important for the rest of his life. He took the lesson to be fair with any complaint made to him. He makes it a point to assess a situation rather patiently and empathetically than being judgmental quickly.

There is an interesting anecdote about Vinod’s opting for an engineering course after completing his twelfth standard in CBSE in 1966. He narrates, “ I really had no interest in engineering at all. I did well in my higher secondary CBSE exam and was interested in physics, because back in the mid-60s, there was a lot of talk about space programmes.

Russia had sent a cosmonaut into space in a spacecraft. America was trying to take a step further and land a man on the Moon. On weekends, I would go to Connaught Place (in New Delhi) and pick up old books on physics, space science, etc, from the booksellers selling on the floor of the corridor between the inner and outer circles of Connaught Place. They used to sell those books at a price as low as one rupee to five rupees. Those were the only books that I could afford to buy then. However, I developed my interest in physics by reading those books and enrolled in Delhi University to pursue graduation with Physics Honours. My brother, a physician, convinced me to become an engineer because he thought an engineering degree might lead me to a more rewarding career than a Physics Honours degree. So, I became an accidental engineer. Looking back, I’m glad that I am, because I got certain opportunities. I found my passion in semiconductors, which is also related to physics. I came to America and did my master’s degree in solid state physics, which was basically the physics of semiconductors. So, eventually, I ended up doing what I wanted to. Though itt took a little bit of a detour for me to get there.”

Given the delay in the decision to pursue an engineering degree, only a handful of colleges were available for admission. Eventually, Vinod got admitted to the Delhi College of Engineering for a BE degree in Electrical Engineering. “I felt lucky to get admission in electrical engineering, but I didn’t particularly care about electrical engineering. I didn’t find the course interesting because there was not much physics to talk about. However, in the fourth and final year, the college decided to start teaching electronics as an elective. Fortunately, I was among the thirty students who were selected for this new course. A professor from Illinois came to teach electronics engineering, and subjects such as communications, microwaves and related stuff were taught and I found them very interesting. I thoroughly enjoyed those last two years of my college and really learned a lot,” Vinod explains.

| “I think entrepreneurship is probably the most challenging job, as there are nine hundred and ninety-nine reasons for failure. If you still want to succeed, you have to be a little bit crazy to do this. But if you succeed, it’s very exhilarating and rewarding. Once you have tasted the fruits of entrepreneurial success, you will never go back to being anybody but your own boss, pursuing new ideas, and backing innovative startups.” |

| —Vinod Dham |

Being part of an engineering institute, where students boasting much higher grades came in from all over the country, Vinod felt out of place in the initial days. At the end of the first year, there was a common exam for all the new students to select those who would qualify for a merit scholarship. Vinod decided not to take that exam, for fear of not doing well.

Vinod says, “Therefore, on the day of the exam, I decided to skip college. My father asked me why I was not going to college. I told him I didn’t want to embarrass myself because the other students were expecting very high scores. Since the exam was optional, he urged me to take it as there was no downside. When the results came out, I was pleasantly surprised to outdo those I was afraid were way ahead of me. This helped build my confidence sky-high. I felt I could climb the ladder of life as successfully as anybody else. That was really a game changer for me!”

Vinod broke the stereotype of a good student repeatedly throughout his educational life. For example, he did not attend classes that were not interesting enough for him. He remembers one instance where his professor made a joke of him by saying, “Mr Dham, you’re early for the next class,” when Vinod attempted to enter the class towards the end.

However, the impact of not attending classes went far beyond the joke as Vinod had to face the same professor in the final examination. In spite of all his answers being correct, he received poor marks. The professor explained that Vinod did not deserve good marks because of his poor attendance. He says, “See, I was not judged on merit or knowledge, I was judged based on my lack of discipline for not attending classes. So, this has stuck with me and I actually use it as a lesson in my life.“

Soon after completing his engineering degree in 1971, Vinod began his professional journey. He mentions, “Believe it or not, none of the big Indian companies like TCS or Wipro—or similar multinationals like Nvidia, AMD, Broadcom, and Intel—offering thousands of jobs in electronics today, existed in India at that time. The word startup did not even exist in the vocabulary of India. The few companies that existed in this sector were either Philips, which was basically selling radios in India, or Televista, which used to make television, or one or two similar ones. So, I had only a few options. However, an invisible hand has always guided me in my life. Somehow, I met a young man who was my brother’s friend. He recommended my name to his company and, finally, I got a job.”

Vinod began his career with Delhi based semiconductor (transistors and diodes) manufacturer Continental Devices India Limited, one of India’s only private silicon semiconductor companies at that time, who had collaborated with Teradyne Semiconductor Company, USA. The company was established in 1969 by Gurpreet Singh, an alumnus of the London School of Economics.

While remembering Gurpreet Singh, Vinod mentions Singh’s hosting Robert Noyce, the co-founder of Intel, at his home. He recalls, “The saddest story Sardarji told me was that he took Intel founder in 1969-70 to the then Department of Electronics, Government of India, as he wanted to start building chips in India. However, the Indian government told Bob Noyce that he could build only 200,000 chips per year. We all know, that a fab produces millions of chips per year! Moreover, it is ridiculous to put a limit on chip production, because the more you make, the cheaper you make, and the better you make.

“Bob Noyce went to Hong Kong to build a factory and India missed the semicon opportunity just because of the license raj or an inappropriate regulatory environment in India. We missed the bus in a big way, for a long time. I was hurt to learn this little-known tidbit about how we missed an opportunity. Had we capitalised on it then, it would have put India ahead of Taiwan and China, and we would have been one of the foremost countries along with the US.”

Building a professional life

At Continental Devices, Vinod was a part of the early team that put together a facility in Naraina Industrial Area, New Delhi, and worked there for four years. While he worked at this company, his love for semiconductors grew further. He found the subject quite interesting and felt that he needed a deeper understanding of the physics behind the behavior of the semiconductor devices. This quest for learning prompted him to pursue higher studies.

In 1975, Vinod left Continental Devices to pursue an MS degree in solid-state physics from the University of Cincinnati, in Ohio. This decision was prompted by the suggestion of S.S. Madan, the then general manager of Continental Devices. He was a semiconductors expert who had returned to India after spending many years working for Philips Semiconductors in Holland. “This turned out to be the second game-changing decision of my life,” Vinod explains.

Back in 1975, the government of India used to allow only eight dollars as foreign currency to the Indians going to the United States. As a student, Vinod could get an additional twenty dollars for books after approval of the Reserve Bank of India. He remembers waiting at Reserve Bank’s Parliament Street office in New Delhi for two days without any fruitful outcome.

Then his elder brother, the banker, offered support for arranging that money. However, Vinod refused that help after knowing that his brother had to approach the approving officer. He says, “I was offended that I needed his help to get a simple job done, that I was quite entitled to. But India those days was more about whom you knew and not what you knew.”

“So, I actually reached America only with just eight dollars in my pocket. After reaching there, I went to the foreign students’ office. There was a student counselor who had been corresponding with me for a year. She asked what she could do for me. I asked about my research assistant job. That was supposed to get me 325 dollars. She said I wouldn’t get that money until I did a month’s work. I told her I needed at least 75 dollars for rent and 15 dollars for health insurance, even though I needed some more money for food. She went to a room and came back with 125 dollars in cash. It was a distress fund. Later, I paid it back at zero percent interest at about 25 dollars a month, after getting my salary.

“My first salary in the USA was USD325,” Vinod recalls. “Fortunately, within nine months of being there, the dean offered me a temporary teaching position to teach in the semiconductor lab, since the professor responsible for teaching in that lab was on a year-long sabbatical. Since I was the only student who had a semiconductor background and understood how chips are made, packaged, and tested, and the entire gamut of things, I was offered the job. Initially, I was quite reluctant to accept it as I had never taught before and was not confident that I could really stand in front of people and teach. However, my advisor encouraged me and I accepted. I very much enjoyed my teaching assignment and the perks that came with it. I also felt like a king as my salary was raised to 625 dollars, the biggest jump I ever had,” he says.

Vinod believes in learning by doing. He followed the same principle in his teaching as well. The university compiled a book based on his lectures. “I got to know about that book from the students who joined Intel after graduating from that school. They used to tell me that they had studied my book. I was surprised as I’d never written a book; I’d only compiled my lectures. It turns out the school had taken those and made a book out of them, and they were charging them 20 or 25 dollars. After finding this out, I called my professor and jokingly said that they had not paid me royalty for my book. He just laughed off. They were wonderful people,” he says with a smile.

Vinod enjoyed his study days in the USA thoroughly. “I think education in America is an absolutely enjoyable experience. Especially for the Indians, it is a piece of cake. That’s why all the Indians who come here just fly high,” he opines. In India, I felt the professors were finding reasons to filter you out; here they were genuinely trying to help you learn. He completed his master’s degree with ease.

However, even before completing the same, he got a chance to experience the “true American way of life,” as he describes, through an invitation from one of his fellow students. “It was the first American house that I ever went to. I was blown away because I had always been staying in an apartment, sharing a small room with another student. But this fellow who invited me had a proper house with many bedrooms, full of music and fun.” That experience allured him to taste such a life.

“I remember going back to my advisor and telling him that I would prefer not to do a PhD. He got very upset with my decision because he had gotten some grants from NASA for my research work. I decided to continue research as per his wish as I knew that I wouldn’t get letter of recommendation for a job from him, if I offend him. There was no concept of an H1-B visa then. Your professor had to write a letter of recommendation for you to go to a company to get practical training. So, I went back and started working on the PhD again. But my advisor came back to me even before I finished my work. He asked me to go for interview with NCR Microelectronics, which was a big sponsor of his semiconductor lab. NCR had reached out to him for a trained resource to solve some issues in their important project and, again, my name showed up at the top because I was the only student with work experience in semiconductors. He promised me that even if I did not get selected, he would let me go after my master’s degree. Since I didn’t have a car, he drove me for the interview. Fortunately, I got selected and accepted the job,” Vinod says.

While working with NCR, Vinod came across a person from Bell Labs, which is considered the Mecca of research in the USA. “That person had a great liking for me. He taught me everything about research, invention, and innovation. Together, we created a leading edge non-volatile memory, the precursor to today’s flash technology used for storing photos in iPhones. We co-authored papers and patents,” Vinod recalls.

While presenting such a work paper on the novel non-volatile memory on behalf of NCR Microelectronics at an IEEE workshop in Monterey, California, Vinod met Bill Johnson, a director at Intel. Bill was quite impressed with his presentation. He offered Vinod a job at Intel and the rest is history.

| “I am quite impressed with the vision Honorable Prime Minister Narendra Modiji has set for the growth of the Indian electronics industry. Ashwini Vaishnawji, Minister of Railways, Communications and Electronics & Information Technology in government of India, and Rajeev Chandrasekhar, Minister of State for Electronics and Information Technology of India are quite serious and have the domain knowledge to lead this effort for carrying out Modiji’s vision. It really inspires me to be part of the team to make this very important mission succeed. It’s a strategic imperative for India. It’s not just nice to have or good-to-have, it is a must-to-have,“ |

| —Vinod Dham |

Becoming ‘Father of the Pentium Chip’

In 1979, Vinod began his journey at Intel as an engineer in the non-volatile memory team to co-invent Intel’s first flash memory (ETOX) along with other two team members he lead. However, his aspiration was to become a general manager rather than continue with R&D work. Thus, he moved to Intel’s business side by joining a task force to manufacture Intel 386 microprocessors. Unfortunately, Intel 386 was yielding a mere half a good die per wafer with a potential of 50 dies on the 15cm (6-inch) wafer. This issue was a big threat to Intel, since its competitor Motorola was already in high volume production.

Vinod worked as a part of the task force under Craig Barret, who later went on to become CEO and Chairman of Intel. The task force successfully pointed out flaws in the way the silicon process was architected. Vinod’s contributions to this very important success in enabling ramp up of Intel 386 catapulted him to manage Intel 386 compaction, a follow on to Intel 386, and then take over Intel 486 design mid-stream and make it one of the most successful products, putting Intel on the top.

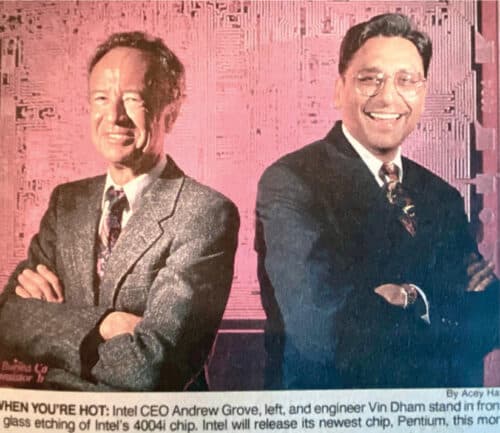

Vinod helped built a multi-billion-dollar business for Intel as the general manager of Intel 486 product line, before being requested by then CEO, Andy Grove, to step out to start leading the next-generation Intel microprocessor, internally known as P5—until it was named ‘Pentium’ at its launch. Vinod is known as the ‘Father of the Pentium Chip’ for his contribution to the development of Pentium and making it the most popular microprocessor in the world! Thus, a leader was born.

Vinod mentions, “I learned leadership from Andy Grove, who was the leader of Intel. I actually learned from him by watching, observing, and asking. Then, I applied the learning in my own leadership style.

“Though I did not have to create a vision, I saw people like him and Gordon Moore creating the vision for the company and then articulating it in a very clear, simple way, that even a security guard would know as to what was crucial for success of the company at any given point.”

While describing his success in leading Pentium, Vinod says, “It was extremely challenging, very fulfilling, and game-changing in many ways for me. Not only it gave me worldwide visibility, but it also helped me subsequently in many things that I’ve done since. It gave me enormous confidence to deal with very complex projects and situations. These things are important for discovering your own self, and to know what you are capable of.”

As a leader, Vinod prefers to be very crisp and clear with his team about what they want to accomplish. Then he develops a strategy for accomplishing the same, puts together a plan to support the strategy, and divides the plan into actionable objectives on monthly and quarterly basis. He ensures all team members are on the same page and marching down to the same goal.

Nurturing family life and entrepreneurial dream

Vinod began his family life simultaneously with his journey at Intel. He got married in 1980, just six months after joining Intel. It was an arranged marriage. His wife is from Chandigarh. She was doing her PhD before their marriage. Vinod says, “Since we got married within three weeks of having met each other, she did not get time to finish her PhD, instead she received her master’s of Philosophy in English.

They have two sons. The elder son is an entrepreneur, making a go of his startup. The younger son is a venture capitalist; he was recently featured in the ‘40 Under 40’ list. Vinod is a happy grandfather with one granddaughter and one grandson.

Along with living a happy family life, Vinod continues nurturing his entrepreneurial aspirations. He left Intel in 1995 and joined the microprocessor startup Nexgen as COO. Vinod’s insight helped Nexgen in successful acquisition of the company by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), an emerging leader in the semiconductor computing industry.

Gradually, his interest shifted beyond microprocessors. After spending one year in AMD, he started the communications processors startup Silicon Spice and worked as its CEO and President. His leadership helped develop the first multichannel Voice over IP (Internet protocol) chip, part of an eco-system that enables applications like WhatsApp used by billions around the world to make phone calls. In 2000, Vinod sold Silicon Spice to Broadcom for $1.2 billion in an all-stock deal.

Please register to view this article or log in below. Tip: Please subscribe to EFY Prime to read the Prime articles.