From text to graphics, from keyboards to mice to touchscreens, we have come a long way. Gestural interface comes next in this logical progression of human-machine interfaces (HMIs). The journey has already begun. We have advanced gesture sensors and software stacks to understand these gestures and use these as inputs for various applications. Products and projects like Microchip’s GestIC, Nintendo Wii, Intel’s RealSense, Leap Motion, Google’s Soli, Microsoft’s Kinect and Handpose, and Gest gloves do show some promise.

Many industry watchers also believe that the future of the Internet of Things (IoT) depends on the success of gesture based interaction because these devices will be very deeply intertwined in our lives, and we must be able to interact naturally with these if we are not to go crazy!

However, most of today’s gesture interfaces have some constraints. Many work together with touch and not independently. Others might require you to sit in front of the computer within the acceptable range, wear a gesture-control device, ensure that the room is properly lit and probably even train the computer to your hand size and movements.

Recall scenes from the movie Minority Report and you begin to wonder whether the existing technologies are anywhere close to that kind of intuitive gesture control. Can you grab files in the air and throw these into folders? Would it be possible to sift through and organise tonnes of data within minutes? Would it be possible to use gestures to simulate a plan and implement it?

There is abundant research happening around the world to enable all this, and we will probably be interacting with computers using purely gestures sometime in the future. However, would that really be necessary for all of us?

Not all tech works for all devices

Some experts feel that gestures might not be needed for all kinds of computing. Take the example of touchscreens. While initially not very successful in larger computers, these have evolved into de facto tech for smartphones and tablets. Gesture based interfaces too might make it big only in such specialised applications. For example, handling files on a laptop or doing something on the phone are more of personalised tasks. You do not want to be gesturing to such personal devices, drawing everybody’s attention to what you are doing.

However, in more collaborative environments, or when the user has disabilities that hamper the use of regular user interfaces (UIs), or under demanding environmental conditions, gestures might be really useful. For example, a scuba diver could do with a robot assistant that understands gestures. He or she could point at objects and instruct the robot to click photographs from specific angles.

Or, let us say a health-awareness video is being shown to a group of illiterate people in a village. The viewers are not tech-savvy, the environment is likely to be noisy and the people might even speak different dialects. If the computer could understand their gestures to carry out instructions like replay or volume control, it might improve the effectiveness of the presentation.

When you are on a snowy peak wearing heavy gloves, it might not be easy to use a touchscreen. Gesture computing could be a life saver then. Baby monitors, computing systems for people with disabilities, support systems for people working under dangerous environments and more could also work with gesture systems.

Let us look at some projects that aim to improve the use of gestures in such specialised applications.

Working with the tongue

When we think of gesture based computing, the first thing that comes to mind is people with sensor-studded gloves waving their hands this way and that. But how do people with paralysis communicate with their computer, when it is not possible for them to move their arms or legs? Such patients can only use head, tongue and eye movements as inputs for gesture-interface systems. Of these, tongue based systems are popular for paralysis patients because tongue is a flexible organ that can be used to perform several gestures. It is also considered to be intuitive and more reliable because the tongue is controlled by the cranial nerve, which is embedded in the skull and is not easily damaged during spinal cord injuries.

However, current tongue based input systems are very intrusive. These often require magnetic sensors to be built into dentures or artificial teeth, or for contact with the skin using electromyography (EMG) sensors. This can be quite uncomfortable as EMG electrodes can cause skin abrasions in the long run.

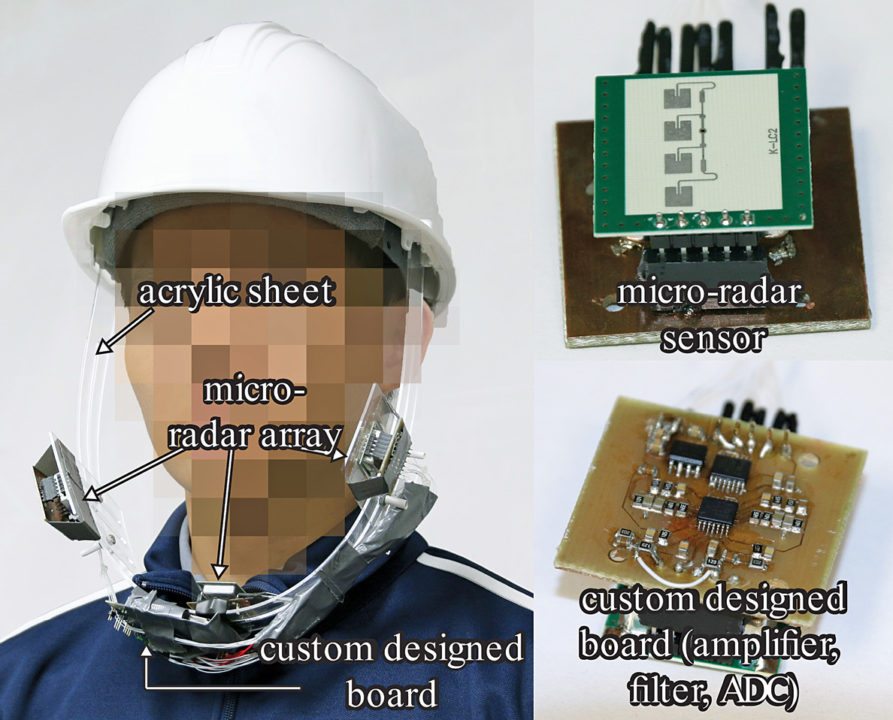

To address this problem, researchers at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, USA, recently proposed a novel contactless sensor called Tongue-n-Cheek, which uses micro-radars to capture tongue gestures. The prototype system is in the form of a helmet to be worn by the user. It comprises a sensor array with three micro-radars bolted to thinly-cut acrylic sheets attached to the helmet.

The team has fabricated a custom-designed printed circuit board (PCB) to house a filtering circuit, an amplifier and an analogue-to-digital converter. The micro-radars act as proximity sensors to capture muscle movements when the patient performs tongue gestures. Tongue-n-Cheek system then converts these movements into gestures using a novel signal-processing algorithm. Tests have showed that the system could decipher tongue gestures with 95 per cent accuracy and low latency.

Wish you a safe drive

Not having to fumble with buttons and levers would be a huge help for drivers and, understandably, auto-makers are exploring the use of gestures to control car functions. This was one of the prominent themes at this year’s Consumer Electronics Show (CES 2016) held at Las Vegas, USA, as well.

Intuitive infotainment. BMW showcased a few gesture controls in its 7-series, achieved through sensors on the cabin roof, monitoring the area near the infotainment panel. The controls, which experts have reviewed favourably, enable you to change the volume through a circular motion of the index finger, answer or dismiss a call by pointing straight or swiping right, and configure one other setting of your choice by swiping down two fingers.

BMW also showcased AirTouch, a futuristic UI implemented in its prototype Vision Car. Building on the existing gesture-recognition system, AirTouch lets both driver and passengers to control the car’s features with gestures using sensors that record 3D hand movements in the area ahead of the infotainment panel. The display is also rather large and panoramic, enabling users to point to required menu choices more easily.

AirTouch is intuitive, in the sense that it attempts to anticipate the next command and reduces the steps required by the driver to complete a task, with minimal distractions. For example, as soon as the driver activates the phone with a simple gesture, the system automatically opens the contacts list so that a call can be placed easily.

Volkswagen also demonstrated some gesture features like controlling the infotainment panel, opening and closing doors and more.

Effortless control through eye movements. Quantum Interface and EyeTech also unveiled technologies that could help intuitively control cars, gaming systems and other devices by simply moving the eyes. In a pre-CES interview, Jonathan Josephson, COO/CTO of Quantum Interface, commented, “Interacting with technology should be fun and easy. It should also be natural and intuitive. If you think about it, we look with our eyes to see what we want before we do anything else.”

Together with EyeTech, they unveiled what they claim to be the fastest and most natural way to interact inside the vehicle. Quantum Automotive Head-Up Display (QiHUD) is a solution that combines eye tracking and predictive technology for easier adjustment of controls while driving. The eye-tracker detects the direction of the eye movement, while user intent is predicted and confirmed with touch or voice.

Adjusting seats. Infotainment apart, another task that often distracts drivers is the pulling of levers to adjust seats. Scientists from Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute for Silicate Research and Isringhausen GmbH have developed a seat that can be moved and adjusted using simple gestures. The prototype seat features a gesture interface located in a panel along its side. To begin adjusting, drivers activate the system by pressing on the panel’s synthetic covering, which veils a piezoelectric sensor. This kind of on-off prevents the system from accidentally reading random hand gestures as commands.

Once the system is powered on, instructions are read using proximity sensors that detect changes in the surrounding electrical fields caused by the driver’s hand movements. Drivers can adjust the seat forwards or backwards, upwards or downwards, inclination of the thigh support or backrest simply by brushing fingers across the seat, which, in turn, activates the required motors. It is also possible to retrieve frequently-used settings by repeated pressing on the console. This is helpful in cases where a group of drivers use the same car. The researchers plan to commercialise the technology very soon. (Contd.)