The government of India has come up with a 760 billion rupee layout plan for semiconductor and display fabs. How do the industry heavyweights perceive this plan? What are they doing to be successful, and what’s their advice for smaller companies?

A tweet “Intel-Welcome to India” posted by India’s IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw sent ripples down the core of the semiconductor ecosystem of the world. This tweet was a result of Intel’s Foundry Services president Randhir Thakur praising the government of India for the recently announced 760 billion rupee India Semiconductor Program. The aim of the Program, similar to the National Electronics Policy and every scheme announced under it, is to make India the hub of semiconductor manufacturing. The Program attempts to set up a semiconductor as well as display manufacturing ecosystem in India.

India currently depends fully on imports for meeting its semiconductor needs, but that has been said a thousand times before. What’s different this time is the intent, and the list of leaders and India based corporate houses joining the struggle to set up a semiconductor and display base in the country. Their aim is the same, and they all want to make sure that India does not miss the bus of semiconductor manufacturing once again.

“The recently announced comprehensive program for the development of sustainable electronics and display ecosystem in the country with an outlay of `76,000 Cr confirms the PM’s vision of AtmaNirbhar Bharat, and positioning India as a global hub of electronics system design and manufacturing. Displays constitute a large portion of the bill of materials of many high-volume electronics products. India’s display market is estimated to be $7 billion, and it could grow up to $19 billion by 2025. Current demands are met exclusively through imports,” says Sanjay Agarwal, President of ELCINA and MD of Globe Capacitors.

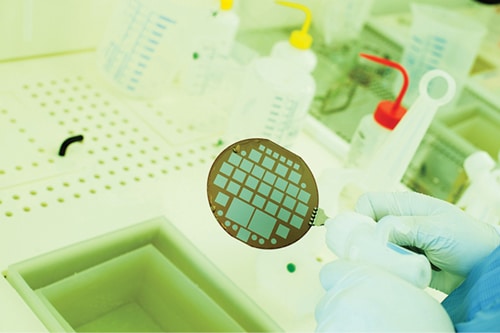

Semiconductors and display units are generally referred to as the soul of modern electronics. These are also said to be among the top factors that are driving the ongoing Industry 4.0 revolution. The challenge is that both semiconductor and display manufacturing require huge capital investment, and these need to be done with the help of most modern technology. Rapid changes in technology further require investments for sustenance and gestation.

“The benefits of establishing this industry includes greater than $11 billion dollars domestic value creation, display export opportunities of up to $10 billion, and domestic employment generation of more than 200 thousand,” adds Sanjay.

Amrit Manwani, MD, Sahasra Electronics notes, “The leadership of India, in the past six to seven years, has rightly highlighted and worked on the importance of electronics manufacturing. Several incentive schemes like EMC, SPECS, and PLI have also been introduced. But for the first time the Ministry of Electronics under the leadership of Ashwini Vaishnav and Rajeev Chandrasejhar has truly engaged with the industry to recognise the challenges and mitigate them through various reforms.”

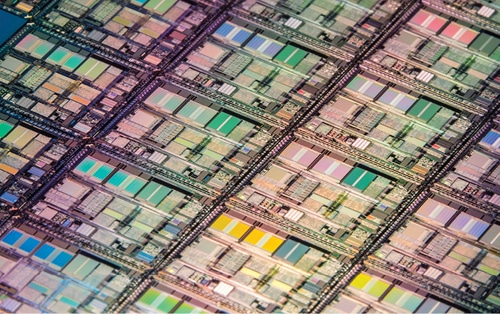

“So far, we have virtually had the absence of semiconductor manufacturing in India, even though we had strength in semiconductor design where we do designs for the entire world. Now, because of strategic reasons and also because of the fact that our import bill will only keep on mounting if we don’t have a semiconductor foundry in place or an IDM in place, this is why there is a renewed effort in bringing semiconductor manufacturing into India. There have been efforts before but what is different this time is, firstly the size of the Indian market is today standing at 3.5% of global electronics manufacturing. We expect it to become 10% of global electronics manufacturing in the next four to five years. As more and more products get manufactured in India, one way is to keep on importing the components. The other way is that, now that there are strong brands here who control the supply chains, if a fab is there, then they may well be inclined to get their memory and logic pieces out of India as well as power devices,” says Saurab Gaur, Joint Secretary, MeitY.

The government and the heavyweights

The government and the heavyweights

The road to making India a hub of semiconductor and display manufacturing is not going to be an easy one. Not only will the players deciding to join the game will have to take lessons from the past, but players from the equipment, materials, designing, services, and all other verticals of these two ecosystems will have to work together to make India the hub of manufacturing these.

“The global conglomerate has started seeing India as a place now. Government has walked the talk and now is the turn of the private players to showcase what they can do. Indians are very intelligent, and you may see very cost-effective TVs, smartphones. and more consumer goods getting manufactured and exported from here. It is all about backward integration and we all know what has happened in the automotive sector in the country. Hyundai exports cars at prices it cannot achieve in its home country Korea,” says Pranav.

He adds, “The scenario at the moment is now or never as the country is already on its way to have bigger exports bills of components than oil. It’s not a short-term game. The horizon should be for at least 20 to 30 years.”

Taiwan and China are the perfect examples of the semiconductor and display fabs being a long-term game. While the former is now a world leader in terms of semiconductor manufacturing, it still keeps investing in developing the latest tech. The latter, which started its semiconductor journey about a decade ago, is still investing in huge numbers to make sure it becomes a world leader in the next few decades. The government of China helping semiconductor companies in the country is not a hidden fact at all.

“Money going into these initiatives is hearty as the returns will take much longer time. But then it is a very stable business over the long term. You can also grow very rapidly. I have myself worked for companies which were a manufacturing start-up and they became a multi-billion dollar business over time,” says Raja.

The Tata’s are said to be putting more than 3.5 billion rupees for setting up an ATMP/OSAT in the country. Raja Manickam, who had earlier founded Tessolve, was roped in by Tata last year to head the project. Several other biggies from the semiconductor ecosystem have also joined Tata’s in the new venture. “In my mind, all of this has to play together to make India the favourite destination for manufacturing electronics,” feels Raja Manickam, CEO, Tata OSAT.

Vedanta Group joining the initiative to make displays in India is probably one of the best developments that the Indian electronics industry has come across in the recent days. Of course, the Tata’s have already forayed into semiconductor packaging but Vedanta Group announcing an investment of 600 billion rupees for chip and display manufacturing is the cherry on the cake.

“We want to enter into integrated fabs, both in semiconductor as well as display. We plan to set up internationally competitive facilities. Initially there will be support from the government, but we will achieve leadership in due course of time. Apart from capturing the domestic market, we are also going to focus on export plans. We don’t just want to achieve fabs, but we want to enable India and Vedanta as Electronic Hubs. That should bring in the entire ecosystem into play,” says Pranav Komerwar, CEO Electronics Display & Semiconductors, Vedanta Limited.

The group already has a presence in EMS and PCB assembly verticals of the electronics ecosystem. It is of the view that OSATs and semicon fabs can bring in good value addition. “Out of about $20 billion investment, Vedanta will be making $8 to $10 billion in the OSATs and semicon fabs segment. We want to work under Make in India and put products in the world under our domain,” says Pranav.

Reliance Industries Limited has already started work on constructing the Dhirubhai Ambani Green Energy Giga Complex. Located in Jamnagar, Gujarat, the complex will house not one but four gigafactories. These would include an integrated solar photovoltaic module factory, an energy storage battery factory, an electrolyser factory, and a fuel-cell factory for converting hydrogen into motive and stationary power.

“The confidence behind that (India’s share in global electronics manufacturing) is because of the interest global champion companies have shown to participate in our PLIs for mobile, where Apple and Samsung as two big players have committed huge manufacturing investment into India or in IT hardware where, again, we have Dell, HP, Acer manufacturing in India,” notes Saurabh.

There are four parts of the scheme. The first one is regarding semiconductor fab where the government is committing almost $10 billion for the overall project. For fab alone it is committing 500 billion rupees, which is almost $7 billion; three or three-and-a-half billion dollars for each fab. Then there is display fab scheme, where again there are various form factors of displays. In the compound semiconductor, that is, in the RF and power category, there already are companies who have registered on the portal. The government, as per Gaur, has received good response in semiconductor packaging as well. Fourth is the semiconductor design linked incentive scheme, where the government has already received 25 odd registrations on the portal.

Saurabh adds, “So we have full registration on the third part and on the first two pieces also have a limited window available, and there is a lot of homework that is required, and we are in constant touch with the potential applicants, and we hope to get a good response in that as well.”

The road ahead

Though biggies like Tata and Vedanta have announced big investments and plans, this is not the first time that the country is looking to establish a local ecosystem for semiconductor manufacturing. There has been more than one attempt in the past. As a matter of fact, Vedanta itself had to back out from setting up a display manufacturing unit in India a couple of years ago. The manufacturing in other sectors of electronics has also not come to India as was expected in the past.

“Corning’s display glass manufacturing strategy involves disciplined growth to ensure that the global display industry and end-market demand are aligned. One example of disciplined growth is our track record of co-locating with our customers. Our glass plants are directly connected to our customers’ fabs. This eliminates packaging, maintains the glass quality, and reduces costs. It also makes us an irreplaceable part of our customers’ operations. We are excited about what is yet to come in the display business and by Corning’s role in driving this industry ahead,” says Sudhir.

“I believe the impetus is now on value adding. First of all, anywhere the assembly section would start like an EMS play, which might not be much of value add but is needed. The PLI schemes by the government are driving the low-investment assembly plants. Today the demand is huge. Our chairman always says that even if you exclude China, and if you count the population of the countries neighbouring India, it still counts for one-third of the world’s population. Forget these countries, the majority of homes in India still do not have TV in their house. 500 million Indians do not have a smartphone. This is just the domestic demand I am talking about. Companies and people migrate only when there is a core mass,” says Pranav.

He adds, “Display and semiconductor fabs can only come when there is core mass. They act as anchors. There is no place in the world where these industries have come up without the presence of these anchors. We find that the policy is excellent for fab set-up. The third dimension now is to get into quick movement. One way is to invent on our own and do it in 10 to 20 years, while the other way is to partner and learn from the masters.”

The technology partnerships would indeed be crucial for companies setting up display or semiconductor fabs in the country. China, Korea, Japan, or the United States of America have been successful and profitable at what they do because the governments, and the private players, never hesitated in collaborating outside their borders. Yes, they assessed all the risks and possibilities, but they were clear from the beginning about their success plans going through the bridge of collaborations, partnerships, and technology transfer.

“The demand is huge right now worldwide with AI coming in and trying to mimic the human brain. Today, AI doesn’t even match 1% of the human brain, so you can imagine how far we have to go. Then we have 5G companies, then we have edge computing—so there are so many new areas which are driven by all the applications in many segments, whether healthcare or industrial or agriculture. All these applications need more and more semiconductor chips to be built,” shares Sambit.

He adds, “I think India can lead in the areas where there are huge demands in the country, particularly in the areas of healthcare, education, and agriculture. These are great opportunities for India to tap into. And to make this successful, people have to innovate, be risk taking, and I think the ecosystem needs to come together more cohesively.

“Here we are looking at one mega cluster like Hsinchu in Taiwan. And having that 500-acre space with water and power, semiconductor resources available there; that is a collaboration that is gonna happen with government of India and state governments like a partnership, but also more of a challenge that whichever state comes out with the most policies that single-window the process which makes it easier for companies. Because these are huge resources and capital intensive decisions that companies are going to take and it is not a decision linked to this policy alone. And this policy is not the only thing that’s gonna happen in this sector. The government is also looking at very long term engagement. So, while this 76,000 crore looks like a big number, we cannot stop there. The government is willing to invest more and there’s a reason for that.

He adds, “And my request to the whole industry is that if we can have more risk capital, patient capital driving this. Because hardware is difficult. It’s not like enterprise or software where you have immediate wins available, and you can have ten times valuation available in a year or two. Hardware is a game of patience and it requires much deeper collaboration, and we would want more risk capital to get associated with it, and we would definitely see more emergence of electronics and hardware companies also out of India.”

Opportunity for start-ups and MSMEs

A look at how the heavyweights like TSMC, Samsung and others function immediately draws attention to how they have developed an ecosystem where hundreds, and even thousands of small companies are supporting their efforts. It would not be wrong to say that these heavyweights are in turn supporting these hundreds of small companies. These hundreds and thousands of small companies specialise in one thing and pass on that thing to the likes of Samsung. The key to success lies in finding out how these heavyweights support these hundreds of companies.

“Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and China have different systems. The Korean government and the Chinese government support big companies and these big companies support small companies in turn. The governments in Japan and Taiwan usually support small companies and these small companies in turn support big companies,” says Sung Huk Lee, CEO, TnvisiON.

Then there is more than one example of these small companies becoming a heavyweight over time. The biggest of these is TSMC itself. The company started in 1987 and took around eight years to go public. Additionally, there are examples of smaller companies merging with bigger ones. The news of heavyweights acquiring smaller ones is always there on the circuit. These smaller and bigger companies are able to achieve success together because their thinking process is aligned to each other.

“These companies, from a business or a technology point of view, are able to taste success together because they think alike and they think global. Anywhere you go in the world you will definitely hear about the Samsungs and the LGs. In present times you will also hear about the companies that are supporting them. I think the message is to always have a global part in your approach. Whether you are thinking of supporting Tata or Vedanta, you should always think of marketing yourself globally as well. That is what is going to sustain,” advises Raja.

“What I would like to see on a personal level is that a lot of product innovation happens in India. End product innovation and end device development needs to happen in India too. Because a lot of start-ups today focus more on applications and software, and this focus has to now change into devices, which makes more sense to India. Given the kind of chip manufacturing capability that we have we can do even more innovation. Many of the design houses here can make for India. Made in India and Make in India are great slogans but I would also like to see Design for India as a very key aspect coming in and government driving in more incentives and policy in that front,” shares Balaji.

Saurabh adds, “I liked what Balaji said in the sense that if Indian companies are able to grow at scale and engage with these global companies, there is a possibility that in the long term they might be acquired. Even though there is a motive to keep the IP domestic but we would still want more Indian innovation to feed into global companies and hopefully see Indian companies also become global champions in this process.”

Support from academia

Academia will also have to play an important role in enabling India as the hub of semiconductor and display manufacturing. Such companies originating in the likes of Taiwan, China, Korea, and Japan owe a lot of their success to academia, and the scenario in India, as Raja explains, will be no different. Raja further explains that as larger companies avoid taking risks, MSMEs might be the right ones to extend their capabilities and try hands at researching with the right institute(s). One such research agency has already existed at IIT Kanpur for more than 15 years and it is known as the National Centre for Flexible Electronics.

“Whether you look at TSMC, or any other such company, the academia has played a very important role in their success. The key for companies will be to find out how they can collaborate with academia and fine tune relationship building,” shares Sudheer Kumar, COO, NCFlexE, IIT Kanpur.

Satya adds, “I think academia has a very big role to play here by having more MS and PhD programmes targeted at semiconductors. Going back to the success of Silicon Valley, one of the key reasons of their success was how the two big universities, Stanford and Berkeley, worked with the industry and then had the right skills and the right kind of innovation. It was done in collaboration between industry and the academia, so I urge all the academia to do the same thing and drive the innovation spirit.”

He adds, “I think how MNCs like Intel, Samsung, and Qualcomm create alliances in India is also an interesting piece. We have to start collaborating with education institutions and academia more. So, I believe we need to have more programmes on chip manufacturing, because silicon design is complex. But the great news is that we have a good base to start with and we can only get better from here.”

“To make embedded systems and VLSI more attractive, I think there needs to be more core work with Academia because there’s more to it. AI/ML is important but it’s not everything. Unless you get your basic VLSI architecture right, these things won’t work because they operate at a much higher level. So, this would mean that a lot of collaboration from the industry is required,” says Balaji.

The first-mover advantage

The proverb ‘The early bird catches the worm’ will be of much relevance to companies deciding to establish semiconductor and display fabs in the country. As explained earlier, there is a huge market waiting to be tapped and then there is the scope of possible exports as the world has started looking for alternatives to China. India is already a market of ten fabs and there exists none in the country.

“There is a first-mover advantage because primarily this is a capital-intensive industry. It is not easy to make an entry, unless there is good support available from the government. Whoever comes forward with initial two-three fabs in each of the sectors will have an advantage. However, what is also true is one or two fabs in the country are not going to satisfy the domestic market. The early movers will have a better learning curve in comparison to others as it is a very long-term game,” says Pranav.

India, as suggested by most of the leaders, is at once-in-a-generation inflection point. The country has a huge market, a market that is only starting to mature. The next three decades are forecast to be centered around India. Corning’s Sudhir is of the view that good implementation of already announced programmes and a consistency of the same will make India more conducive for conglomerates.

“The devil is in the execution. That is what will keep the market attractive for us,” says Sudhir.

Siddha is a business journalist who is fond of recognising and presenting how tech is shaping up the business world. When not writing about EVs and government policies, she enjoys reading non-fiction for fun. Mukul is passionate about how technology can change lives for good, and skeptical about how the same technology can make matters complicated for the very existence of human beings.

This article was developed thanks to sessions held by ELCINA in collaboration with EFY titled “Establishing an Eco-System For Semiconductor & Display Products in India,” and by Society of VLSI in collaboration with Times Techies titled “Techade For Semiconductors – The Road Ahead.”