Flexible electronics is making its presence felt in almost every field, be it wearable, consumer electronics, medical, industrial or lighting. Still in early development, printed and flexible electronics is also enabling a much-talked-about trend today—the Internet of Things (IoT). Let us take a look at the latest happenings in the area, sneak-peak into the research and development activities and some interesting examples of commercial applications and applications currently under active research.

Large-area and low-cost integration giving rise to real-life applications

In the past year, we continued to see increased interest in the capabilities and technologies related to printed electronics. Printed electronics continues to fit the profile of an emerging technology space as awareness and participation in the area grows. “State-of-the-art capabilities of flexible and printed electronics include logic and memory devices, displays and lighting, thin-film batteries, photovoltaics as well as a multitude of sensors,” says Luisa Petti, PhD student, Wearable Computing Laboratory, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Petti adds, “Recently, efforts have also moved towards large-area and low-cost integration of all these devices into fully-flexible or stretchable systems.” Therefore more and more real-life system applications are being proposed and demonstrated.

It is important to distinguish between hybrid integration of rigid conventional silicon based electronics with flexible electronics and fully-flexible printed systems using only low-temperature materials. Petti says, “On one side, the hybrid approach allows taking advantages of the high performance of rigid silicon technology and at the same time expands its applications using flexible electronics technology.”

A few examples of systems developed employing this hybrid approach are LG G Flex mobile phone, Apple Watch and MC10 Biostamp.

Listed below are some other select examples that show the versatility of printed electronics.

Sleep mask for prevention of diabetic disease. Niche applications are starting to become more apparent within a range of high-value market sectors. Development of a healthcare application that utilises plastic electronics is one such example.

PolyPhotonix, based at Centre for Process Innovation (CPI), has developed a light-therapy sleep mask, Noctura 400, for the prevention and treatment of diabetic retinopathy, a disease caused by diabetes. It is one of the most common causes of blindness in the western world, informs Steven Bagshaw, marketing executive, CPI.

Designed as a monitored home based therapy, the sleep mask offers a patient-centric, non-invasive treatment that can be delivered at a fraction of the cost of the current interventions—laser photocoagulation surgery or intraocular drug injection. Bagshaw says, “With 3.5 million diabetes sufferers in Britain, the technology has the potential to save National Health Service (NHS) £1 billion per year upon adoption.”

He adds, “The key message for flexible electronics from the success of PolyPhotonix is that the company identified a game-changing market application where functional benefits of plastic electronics added significant value to the product. Also, current technological obstacles that are apparent in plastic electronics were not detrimental to the commercialisation of the product.”

Sensor to monitor head impacts in sports. In the last one year or so, the scenario of flexible electronics has rapidly changed. “Main driving applications in this field are related to flexible, rollable, foldable and paperlike displays for the consumer electronics industry,” notes Petti.

Wearable applications with flexible electronics are envisioned not only in the huge display industry but also in the healthcare sector. Here, MC10 is shaping the field with its ultra-thin flexible skin sensor patch, Biostamp.

An interface between human and electronics, Biostamp is a seamless sensing soft sticker, capable of stretching, flexing and moving with the body. Powered by thin-film battery technology, this sensor can measure a variety of physiological functions such as data from the heart, muscles, brain, body temperature and body movement.

Biostamp has been used commercially in Reebok’s CHECKLIGHT, a head-impact indicator that uses a multiple of these sensors to capture head-impact data during play when athletes are unaware of the severity of a blow to the head.

Lighting system that uses flexible circuitry. Cohda, a UK based design studio, has worked with CPI on the integration of printed electronics to significantly enhance the functionality of their wireless Crypsis Lighting product, developing the product from prototype to full commercial manufacture. Crypsis Lighting offers wireless ultra-bright LEDs that can be repositioned and dimmed within a transparent glass panel using an external magnetic control puck. The system is a fully-interactive low-voltage lighting unit and is currently being used within a diverse range of products and markets such as interior design, exhibition design, museum, retail, architecture and contemporary lighting.

Earlier, Crypsis Lighting utilised silicon based electronics for their lighting units. Bagshaw says, “Due to the rigid nature of the circuitry, Cohda encountered a number of issues in research and development including the transfer of power to the light units and voltage drop with the electronics within the light units.”

He adds, “CPI worked with Cohda to use printed electronics to bring flexibility and conformability into the design of their light unit device. These properties enabled the electronics to conform to the surface contact of the glass, resulting in the elimination of voltage drop and an increase in conductivity levels.”

Pure-copper-conductive ink for the wearable world. In November 2014, DuPont Microcircuit Materials (DuPont) introduced their PE510 photonic copper product. PE510 is a cost-effective alternative to silver-conductor inks for a variety of possible applications, and is the newest product in a suite of conductive ink materials specifically tailored for use in certain types of antennae, membrane touch switches (MTSes), radio frequency identification (RFID) and consumer electronics applications.

Stan Farnsworth, VP – marketing, NovaCentrix, says, “This electrically-conductive ink is designed for use on polymeric substrates and reaches optimal performance when processed with PulseForge photonic curing tool from NovaCentrix.” These inks provide designers with higher flexibility to design antennae, enabling a lower total manufacturing cost, while meeting electrical performance requirements.

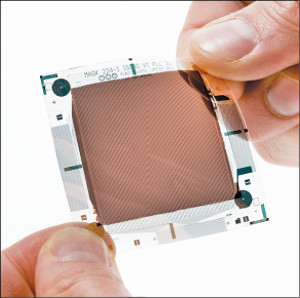

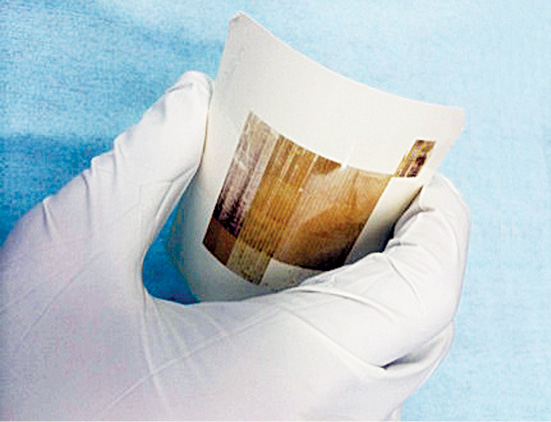

Sensor that could revolutionise industrial and consumer electronics. The fully-flexible approach targets a more unobtrusive and large-area integration of developed systems. A great example of this latter approach includes the multi-awarded image sensor on plastic, unveiled by ISORG and Plastic Logic, which combines the flexible large-area photodetector technology from ISORG and the organic thin-film technology from Plastic Logic.

This opens the way to new applications, ranging from smart packaging, sensor tags for medical and biomedical applications, security and mobility commerce, to environmental and industrial electronics.

Fascinating research and development happening

One of the most challenging goals for flexible electronics is to achieve lightweight and unobtrusive devices, notes Giuseppe Cantarella, PhD student, Wearable Computing Laboratory, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich. Keeping high electrical performances in mind, researchers are now taking big steps forward to integrate with respect to customers’ attitudes and requirements.

He says, “The new trends now go in specific directions to fulfil the market focus. One of these is bio-compatibility for implantable devices that can remotely monitor and improve our healthcare, provide mechanical and electrical stability over time and low cost for the development of a technology that is accessible to most.”

Materials and manufacturing techniques are the two main areas for research. The main focus of research activities in universities and research centres in the field of printable and flexible electronics is in two main directions: the development of new materials with better performances and low-cost deposition, and the study of new technologies and manufacturing techniques on plastic substrates with superior mechanical properties.

“Since next-generation electronics is expected to be conformal to any surface including human skin or human tissues, many efforts have been devoted to establish engineered techniques for conformal electronics,” Cantarella says. A great example of this approach has been demonstrated by the group of Prof. Someya of Tokyo University, where implantable bio-compatible devices have been realised using organic semiconductors.

In parallel to the development of graphene, nanotubes and 2D materials, new material formulations have been introduced. A very new and interesting work is the one on printed liquid silicon on paper, demonstrated by the Delft team, led by Prof. Ishihara at Delft University of Technology. These results could lead to high-performance and low-cost printed and flexible transistors and circuits.

Smart contact lens to inform diabetic patients on blood-glucose levels. A brilliant example of tackling a growing problem of diabetes using flexible and printed electronics is Google’s Smart Contact Lens project, co-developed by Google and Novartis.

Uncontrolled blood sugar poses a threat to people’s lives and could damage their eyes, kidneys or heart in the long run. People with diabetes, more often than not, have fluctuating glucose levels. Sudden spikes or drops are dangerous. To monitor the blood-glucose level, people with diabetes need to prick their finger and test drops of blood at regular intervals throughout the day.

In hopes of finding easier methods to measure glucose body levels, scientists have been researching on an alternate, non-invasive way in the form of measuring tears. With the help of miniaturised electronics, Google is testing a smart contact lens to measure glucose levels in tears using a tiny wireless chip and miniaturised glucose sensor embedded between two layers of soft contact lens material.

This novel contact lens will contain a low-power microchip and a transparent ultra-thin and flexible electronic circuit, and will be used to measure blood-sugar levels of diabetes sufferers. Although these are still early days, Google is also planning to explore the possibility of integrating tiny LED lights to indicate to the user that glucose level has crossed or dropped below a certain threshold level.

Focus on hybrid and purely flexible systems. Most recently, research has also shifted towards system integration, notes Petti. System integration is developing in both the directions of hybrid integration of rigid conventional silicon technology with flexible/printed electronics, as well as the realisation of fully-flexible and/or printable platforms.

The best examples of hybrid system integration can be surely found in the research done by Prof. Rogers at University of Illinois. Areas include flexible, stretchable, epidermal and biodegradable sensors and circuits using conventional silicon technology and unconventional substrates and architectures.

On the other side, a notable example of the fully-flexible approach includes the work by ETH Zürich (or Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich) on lightweight and transparent metal-oxide electronics that can wrap around a human hair. This can lead to fully-flexible and transparent smart contact lenses, as well as many other biomedical applications.

In the field of fully-flexible system integration, the biggest players are Interuniversity Microelectronics Centre (IMEC) and Holst Center, who offer an extensive organic and metal-oxide based technology for flexible thin-film transistors, circuits, photovoltaics and active-matrix organic light emitting diode (AMOLED) displays.

Notable universities involved in research. Globally, key universities in this field are almost too numerous to name with each group working on topics ranging from fundamental science all the way to final product characterisation and prove-out, feels Farnsworth.

He says, “Other than California Polytechnic State University, some other groups doing important work in the area include CPI in the UK, Cetemmsa Technological Centre near Barcelona, Spain, VTT Technical Research Centre in Finland, Fraunhofer group in Germany, Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) in Taiwan, The National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) in Japan and EMSE near Marseilles, France.”

He adds, “Dr Denis Cormier at Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, New York, is doing work combining printed electronics technologies with the still-developing additive manufacturing space.”

Flexible electronics will make a ripple in every possible field

From healthcare monitoring, wearable and skin-like electronics, smart packaging, sensory tags for medical and biomedical applications, security and mobility commerce to environmental and industrial electronics, many novel applications are being envisioned. Petti says, “This is all enabled by the unique selling points of flexible and printable electronics, which include its mechanical flexibility, large-area manufacturing and potential low-cost in volume.”

According to Cantarella, for printed and flexible electronics, the most challenging sector will be medical. He says, “The devices included in this field should be bio-compatible and sufficiently reliable for medical care in order to be able to generally improve healthcare and monitor physical conditions.”

“Even more challenging is the idea to implant such devices for real-time analysis such as digestible electronic components that can be dissolved in the human body,” adds Cantarella.

PragmatIC Printing holds a great deal of potential for the production of new exciting applications within the packaging sector and the development of the IoT.

Bagshaw notes, “The company is developing ultra-thin and low-cost flexible microcircuits that can be easily incorporated into mass-market packaging, and will revolutionise everyday living by providing consumers with real-time information about every aspect of their environment.”

He adds, “Hybrid electronics will give rise to a wide range of new, novel applications such as flexible displays for mobile devices, smart therapeutic bandages for managing and monitoring recovery of wounds, wearable electronics for monitoring and improving performance, wireless medical devices for rapid diagnostics using printed sensors, conformable lighting and intelligent packaging for consumer goods and industrial products, to name a few.”

At a printed electronics conference in the USA, it was predicted that the overall market for printed and flexible sensors is forecast to be worth over US$ 7 billion by 2020.