How has National Instruments (NI) grown from an organisation run by three engineers to a company with 6,600 employees worldwide? What are the basic foundations that the founder of National Instruments laid that have enabled the organisation to grow into a billion dollar enterprise?

Those were some of the questions that drove Rahul Chopra to talk to Dr James Truchard, founder, president and CEO of NI.

Q. What motivated you to start NI?

A. Autonomy was the main idea. I was in Austin and working at the University of Texas. I had just finished my Ph.D and was working in a research lab. I wanted to stay in Austin as I loved the place, so I wanted to create a job that I liked. I realised that to achieve these goals I would have to create a good business.

Plus, I constantly saw a lot of students being forced to leave the city due to limited career options in the region. I wanted to create a company where people didn’t have to leave to grow, because they had a career path. So that was one of the fundamental goals as well. To this day, that goal remains key to NI and that’s why we put a lot of importance on professional growth.

Q. How were the initial times? What were the challenges faced? Any learning that you’d like to share?

A. I worked pretty hard while I was also working on a full-time job so that we could self finance. That’s very difficult to do unless you are in a university environment but Jeff (Kodosky), Bill (Nowlin) and I were able to do this. We self financed the business. As for the initial challenges, obviously the key was for us to pick the right product that we could sell and work on, given our background and circumstances. We did that with our instrument interfaces. What we learned is what we summarised early on through our 100-year plan.

Q. In these days of frequent economic turbulences, NI has a 100-year plan! What’s this plan about?

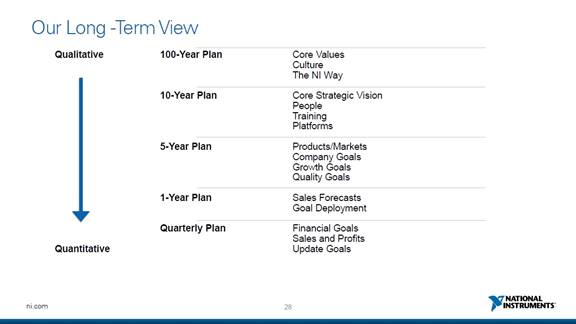

A. Right from the start in the 70s, we always looked at other companies and their culture, and how they operated, to pick up good ideas. It was not until we were to go public that I realised that putting our philosophy down on paper would be helpful when talking to shareholders. So in 1995, I came out with the 100-year plan, which was aimed to frame how we will make decisions.

At the 100-year level, we set the frame for our role in the society. We talk about our philosophy of operations and how it is designed to benefit all the stakeholders.

Then if you look at the next (decade) level, you have the vision of what you are trying to do as a company. When we started, we had a pretty simple vision for creating jobs that we would enjoy and to self-finance the company. It was also the concept of automation of instrumentation that we started, then we went into the vision of what we wanted to do for virtual instrumentation. Vision for us is really a decade timeline.

The next level is the five year time-line, which gets topical, like alternative energy which is important. This term is where we start looking at how fast we can grow in the next five years and so forth.

Then at the one-year level, we look at our goals for the current year, our budgets and so forth.

The overall idea is that we should always look at the long term when we make decisions, and look at the time-line to know when these decisions need to be made and executed.

Q. Any major mistakes made that provided learnings that helped NI grow?

A. One of the most important areas for a vision driven company to focus on, are the platforms that you create, since the software and hardware has to be highly integrated. If you get that strategy wrong, you end up with products that are not that good or don’t fit the platform well. In the mid-90s, for example, we approached industrial automation in a way that didn’t really fit the platform so we also had some forays into products that while they looked similar they were really not vision-aligned.

Also, during the initial phase of NI, we did take on some special projects that, with time, we migrated away from. They helped us fund at that time but they also created distractions. So I always say to follow the vision and execute it well. If we did that well, we did well and if we didn’t do that well then we didn’t do well. Fortunately, we didn’t have too many cases of ‘major’ poor decisions. Overall, we made a lot of good decisions but there were some areas where we didn’t, and these were typically where we didn’t follow the vision as tightly as we needed to, and that compromised the growth of the company.

Q. Typically, entrepreneurs find it difficult to change their role as the organisation evolves. How did you manage this transition?

A. That’s an important aspect, and a very tough thing to do. Your style has to change. As a start-up entrepreneur you have to be aware of all the elements and perhaps the partners who are helping you in that process—whether finance, technical or sales. As the company grows, you have to start delegating. For every challenge, my style has been to figure out one of the officers from the company and then delegate the role. I started with the simplest things to delegate and gradually delegated the more complex roles. The hardest of all, to delegate, is the core strategy and vision.

A basic thumb-rule could be that when you get about 70 people, you have to start working on delegation. When you get to 300 you have to have more formal structure in place, and when you get to 1000 you really have to have a very well formed management structure for each of the functions in place.

[stextbox id=”info”]We should always look at the long term when we make decisions, and also at the timeline to know when these decisions need to be made and executed[/stextbox]

I, for one, delegated things after having figured out how to get things done in those departments or functions. So some of the things I delegated quickly included manufacturing, accounts, and sales and marketing.

I still, from time-to-time, look at the specific elements of products but, more and more, I am now building a team that really understands the vision and key architectures at the top. We actually have a routine meeting of the architects and the visionaries of the company to see whether we are building the products in keeping with the vision that we have.