In radio, multiple-input and multiple-output, or MIMO is a method for multiplying the capacity of a radio link using multiple transmit and receive antennas to exploit multipath propagation. MIMO has become an essential element of wireless communication standards including IEEE 802.11n (Wi-Fi), IEEE 802.11ac (Wi-Fi), HSPA+ (3G), WiMAX (4G), and Long Term Evolution (4G).

At one time, in wireless the term “MIMO” referred to the use of multiple antennas at the transmitter and the receiver. In modern usage, “MIMO” specifically refers to a practical technique for sending and receiving more than one data signal simultaneously over the same radio channel by exploiting multipath propagation. MIMO is fundamentally different from smart antenna techniques developed to enhance the performance of a single data signal, such as beamforming and diversity.

Fading Channels

The presence of multiple reflections and multiple communication paths between two radio terminals cause signal fading impairments to a wireless communication link. There is both selective and non-selective fading. Non-selective fading is the case where the frequency components over the signal bandwidth are dynamically attenuated by the same amount and do not create any signal distortion, but only temporal signal loss. Selective fading is the case where smaller frequency segments of the signal’s spectrum are attenuated relative to the other remaining frequency segments. When this occurs, the signal spectrum is distorted and this in turn creates a communication impairment that is independent of signal level.

For the case of narrow band signals with non-selective fading, the communication impairment can be countered by providing more signal level margin in the communication link or using selection diversity techniques to select the best antenna input based on the relative signal strength. However, in the case on non-selective fading, the signal must be equalized to restore the signal fidelity and expected communication performance.

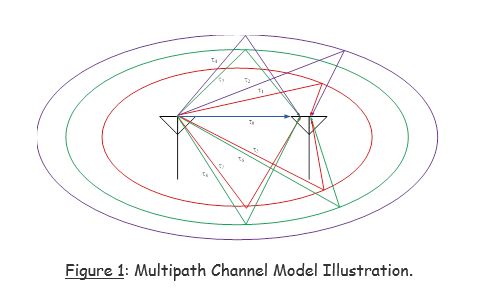

This fading is produced by the arrival of multiple replicas of the transmitted signal at the receiving antenna. The signal replicas are produced by multiple random reflections within the communication medium, such as an indoor communication channel. The multipath concept is shown below in Figure 1 for reference and is based on the notion of an ellipsoidal fading model

Antenna Diversity

As mentioned previously, the effects of this localized and sudden attenuation can compensated by receiving the signal at two different receiver antenna placement locations and selecting the best antenna based on the signal strength or some other receiver performance measure. The diagram Figure 2 illustrates this situation by showing the signal strength at two different antenna placements over communication range and/or time. The point of the illustration is that the signal strengths associated with the antennas are generally not correlated in time and/or space and when one signal is in a null, the other can be found near a maximum and selected for communication.

What is MIMO?

MIMO makes use of the advantages of having several antennas and a range of signal paths. Usually in a wireless link the strongest signal is chosen to make the connection, and all the other signals are filtered out. These multipath reflections come from reflections from buildings and objects, but they are weaker and arrive at different times. In a system with antenna diversity, different antenna pick up the different signals, filter out the noise, and recombine them to generate a single, stronger signal.

Today’s MIMO employs a slightly different approach, but still uses multiple antennas. In the basic MIMO concept for 11n Wi-Fi, the data to be transmitted is scrambled, encoded, and interleaved and then divided up into parallel data streams, each of which modulates a separate transmitter. Multiple antennas then capture the different streams, which have slightly different phases because they have travelled different routes, and combine them back into one.

Each multipath route can be treated as a separate channel, and the separate antennas take advantage of this to transfer more data. In addition to multiplying throughput, range is increased due to the advantage of antenna diversity, since each receive antenna has a measurement of each transmitted data stream.

With MIMO, the maximum data rate per channel grows linearly with the number of different data streams that are transmitted in the same channel, providing scalability and a more reliable link. This robustness allows the system to scale back the current to achieve the required data rate with minimal power consumption.

For Wi-Fi, the modulation is orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) using binary phase-shift keying (BPSK), quadrature phase-shift keying (QPSK), 16-phase quadrature amplitude modulation (16QAM), or 64QAM, depending on the data rate. Different data streams then can be transmitted in the same 20 MHz in the same band, improving throughput. Throughput scales linearly with the number of transceivers.

The multiple signals arrive at the receivers at different times in different phases, depending on the different paths they take. Some signals will be direct, others via multiple different paths. With this special multiplexing, each signal is unique as defined by the characteristics of the path it takes.

The unique signatures produced by each signal over the multiple paths allow the receivers to sort out the individual signals using algorithms implemented by DSP techniques. The same signals from different antennas then can be combined to reinforce one another, improving signal-to-noise ratio and, therefore, the reliability and range.

Perhaps the greater benefit of MIMO is the transmission’s increased range and robustness, as it permits multiple streams. It also helps improve the signal-to-noise ratio and reliability significantly over other implementations.

Types Of MIMO

MIMO is not like the typical smart antenna systems used in cellular networks. A smart antenna uses beam forming to focus the transmitted signal energy toward the receiver to strengthen the signal. Beam forming may provide better range in certain applications, but there are problems with hidden nodes that the basestation can’t “see,” reducing the number of clients that can be supported. Also, the power consumption requirements limit the number of transmit chains. While MIMO can be used with beam-forming systems, there is little point as it relies on the phase shift of the reflected multipath signals.

Many MIMO systems use two transmitters and receivers, but the various standards allow other versions using different numbers of transmitters and receivers. Other possibilities include 2 by 3 (transmitters and receivers respectively), 3 by 2, 3 by 3, 3 by 4, 4 by 3, and 4 by 4. Beyond the 4-by-4 configuration, very little additional gain is normally achieved. The use of two transmitters and three receivers seems to be the most popular, although chipsets are now being implemented to support 4×4 MIMO for the highest-data-rate links.

Transmitting two or more data streams in the same bandwidth multiplies the data rate by the number of streams used. MIMO in the 11n standard also allows two 20-MHz channels to be bonded together into a single 40-MHz channel, which can provide even higher data rates.

With this channel bonding and four streams running on MIMO, a maximum potential data rate of 600 Mbits/s is achievable. Data rates surpassing 100 Mbits/s then can be supported over a 100-m range in hostile RF environments.

Implementation Of MIMO

Improvements in process technology, both for analog and digital devices, have opened up the use of MIMO in many applications. Until recently, very little dedicated hardware was unique to MIMO other than the separate transmit and receive chains. However, the improvements in RF design coupled with process technology mean that multiple transceiver chains can be integrated onto a single chip.

On the digital side, the processing power required to process the data was previously prohibitive in terms of silicon area and power consumption to be handled by the generally available field-programmable hardware. With the latest digital CMOS process technologies, this processing power is available in dedicated FPGA and DSP processors on chip, allowing system performance to be achieved and enhanced through software.

Rather than using the MIMO protocols hardwired into an FPGA, the performance of a DSP, often with dedicated accelerator blocks, is now sufficient to handle MIMO. The MIMO algorithms then can be constantly improved, increasing the reliability of the connection and reducing the power to extend the battery life. While this approach cannot change the number of channels that are used, or the number of antennas, it can enhance the signal processing to boost the performance of the link. So, the link can operate at lower current for the same power budget.

Conclusion

The wireless world needs robust data links. The benefits of MIMO are driving more and more standards from 802.11n to LTE-A to adopt the technology. Using antenna diversity with both multiple paths and multiple channels, coupled with the processing power in the back end, allows a dramatic improvement in the link budget and reduction in the power consumption. By adding a few antenna and more processing power, the next generation of smart wireless systems will be able to combine flexibility while delivering enhanced system performance.

The author is currently pursuing my final year btech in ECE at RSET, Cochin