From the birth of the gunpowder-warfare era, soldiers have been incrementally striving for bigger, more powerful and more accurate guns. Their quest has resulted in the present-day big guns, such as tanks and artillery guns. These big guns—the ‘noisy giant cousins’ of rifles—have the capability to win battles by shattering and scaring the enemy.

(Photograph credit: US Navy, through Wikipedia)

The big guns entered the battlefield as state-of-the-art machines during the First World War and played havoc during the Second World War. But they were just like the shaky grandfathers of today’s big guns. This is because electronics has virtually penetrated all the subsystems of today’s big guns. This penetration has made these guns enormously more capable than their shaky ancestors.

What these guns actually do and how

Though tanks and artillery guns are big and possess long barrels, these are not the same. These are brothers with different purposes. Artillery guns, epitomised by stationary field guns, have longer barrels than the tanks. But here, just for the sake of fair comparison, let us see the electronics present in their track-wheeled brothers—the self-propelled guns (SPGs), which are chiefly area-strike weapons.

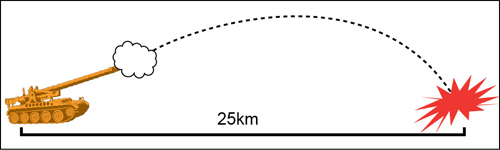

A group of such guns, called battery, is used to bombard an area rather than a single target. With their huge explosive shells, they can bombard a target area situated as far as 30 km away. This is called artillery barrage. An artillery barrage is the most scary and devastating aspect in the battlefield and can flatten structures, vehicles and men. Artillery barrage is the most lethal form of firepower next only to bombing from aircraft. Skilled gunners can engage a single target even as small as a car from as far as 20 km. But the intriguing aspect is that the gunners do not ‘see’ their target.

In military parlance, the common saying is that “you can’t fire at what you don’t see!” But perhaps these guns are one of the very few exceptions as they don’t see their targets. They simply look at the sky and shoot the shells and shatter the targets into smithereens. When these guns face the sky and fire the shells, the shells obey gravity and ballistics, like a stone thrown upwards. The shells fly in a parabolic trajectory and land on the target area.

These guns are deployed 30 to 40 km behind the frontlines and fired. A trooper employed as forward observer, operating along with the frontline troops, is the key. When enemy forces try to overwhelm the frontline troops, commander calls for artillery support in the form of barrage. The observer sees and selects the target, directs the firing of these guns and reports the impact. The guns can fire even over a hill to neutralise the enemy in support of frontline troops, in what is called ‘indirect fire support.’

For the shells to land accurately on the target area, the gun’s elevation and azimuth to be maintained are calculated through trigonometry. The accuracy of the calculation determines the accuracy of a shot! Firing these guns requires a complex alignment process and use of instruments like sextants and clinometers. Simply put, it is more of an engineering process than a firing process.

During the First World War, in the Battle of the Somme, a strange-looking beastly armoured metallic vehicle making ‘clang clink clang’ noises crawled into the battlefield like a caterpillar. It was a British invention that was conspicuously named as ‘tank’ to conceal its real purpose of crossing trenches. As the trench warfare of the WW-I went out of favour of the militaries, tanks got a new job. That job was to be the spearhead of an advancing force. Germans exploited this aspect through their blitzkrieg campaigns in WW-II and tanks came to prominence.