Technology is one of the key routes in bridging the gap between the rich and the poor in countries like India, and can facilitate development in many ways. It can enable free or easy access to education (Cisco Dwara, Khan Academy, The Shuttleworth Foundation), simplify trade and commerce (ITC’s e-choupals), offer employment (Desi Crew’s rural BPOs), provide health services (Wipro’s remote foetal health monitor, Neurosynaptic’s ReMeDi), enhance agricultural yield (RTBI’s agri-advisory system, the Kisan Call Centre) and much more. Hence, technology does qualify as an ‘essential section’ for the population at the bottom of the pyramid (BoP).

This is also an extremely large and attractive market for tech companies to enter.

This is also an extremely large and attractive market for tech companies to enter.

However, building products for this market is not easy. There are multiple factors at play here, from cost and usability to culture and economics. So, let us begin this interesting journey of introspection (the year end is always a good time for reflection) by talking with a few experts on what it takes to build a successful product for the BoP, and then look at some successful examples.

Why make products for the BoP

“That’s an easy one. The answer is size. Simply size. And it’s growing,” asserts Sunil Malhotra, founder and CEO, Ideafarms. “On one side, the share of the wallet of each player in the market is shrinking with increased competition. Overseas markets may not be shrinking but have saturated. India is one of the best hunting grounds for large international companies, not just due to market size (and the fact that it is one of the fastest growing) but also because the semi-urban and rural consumers are beginning to aspire for better lifestyles and therefore better products. Going early to a market that’s ready and eager simply makes good business sense.”

“India and China alone constitute around 40 per cent of the world’s population. Both are growing economies where the spending power is on the rise, but there is a high demand for products that offer value rather than products that command a brand premium. Even in developed countries, a large percentage of the population would fall into the category that looks for products that offer value for money,” says Kantheti Srinivas, director, Processor and DSP Apps, Analog Devices India, a company that offers processors, low-cost MEMS microphones, capacitive touch sensors and other components for products targeted at the mass market.

He adds, “Considering the huge volumes and the opportunities knocking on our doors here, it is important that electronics companies tap the market. However, products in this segment need to offer value and not just be low-cost.”

What kind of products should be made

Markets are shifting from the West. India is predicted to become the fifth largest market in the world by 2025 (according to a recent research by the McKinsey Global Institute). While the scope of the Indian market is clear, what exactly this market wants is a question that needs to be answered.

Alok Mittal, managing director of Canaan India, a leading tech venture capitalist in India, says, “Given the mobile revolution in the country, electronics has become mainstream and is not a preserve of the wealthy. This has also brought in a lot of demand for localisation, which represents an opportunity for entrepreneurs and electronics companies. Handsets and telecom equipment are set to become one of the largest categories of imports for the country, and hence local manufacturing has risen up in the country’s priority list. All these factors make it attractive for companies to invest in this area. Interestingly, mobile phones are likely to become a platform for adjunct electronics devices, such as those used in remote healthcare and education. We have been seeing start-ups in the healthcare domain as well, like companies that are making sensors, which plug into mobile phones to provide low-cost diagnostics.”

According to Malhotra of Ideafarms, “Leveraging the Internet to empower individuals and enable small businesses in semi-urban and rural areas is a foolproof strategy. The increased access to low-cost, high-speed connectivity in rural areas and cheaper access to content in a hyper-local way become powerful change agents in the way information will be delivered, consumed and shared to up the ante in fulfilling basic human needs. Throw in a smartphone and you have a winner. Much of the rural-urban divide is accentuated by a lack of or a lag in information availability. Smartphones, even the cheapest in the market today, will ensure that the consumer is ‘always on’.”

Srinivas also agrees that the mobile phone is one of the most popular products in this segment. He adds that smaller-screen television and audio-visual systems, the home-theatre-in-a-box (HTIB) and solar lighting that use renewable energy address the needs of the BoP too, while energy conservation is also a successful theme for this market.

Malhotra spells out a kind of thumb rule. “From my point of view, it makes sense to go from the bottom up; to create a portfolio of products and services to fulfill basic needs before going after the goodies. My list of ‘basics’ has healthcare, education and finance at a category level; those areas that create better living conditions such as sanitation, clean water, food and energy at the next; and then communication as a means to keeping abreast with the world as well as a channel for feedback, fun and information exchange. Some of the products we saw in the movie ‘3 Idiots’ are pointers to the kind that we need to look at. Not jugaad but concerted reuse of available and existing technologies to take these prototypes to the commercialisation stage with the help of interdisciplinary experts and groups,” he says.

How do companies make a low-cost product

“Addressing the BoP is neither easy nor cheap. Quite the opposite!” exclaims Malhotra. “There’s no intelligence required if all we have to do is to strip a product down to its essentials to reduce quality. I’m also not a big advocate of inventing niche products to go into these markets. These products must be simple, intuitive, safe and sexy, aka world-class.”

Mittal feels that, “In most cases, cost re-engineering is the first important step. This involves understanding the customers at the BoP, and then designing to those specifications. This may involve introducing features (such as ruggedness and long battery life) and eliminating features (such as accelerometers). Since electronics manufacturing is fairly standardised, the functionality drives most of the cost. As you will have noticed, the current examples of BoP products are mostly from the mobile phones’ domain—from Nokia’s Asha series to Micromax’s dual-SIM phones.”

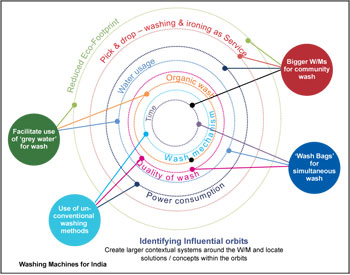

Malhotra recalls, “Earlier this year, Amit Gulati, who runs Incubis, invited me to participate in an interactive session to think through design ideas for a low-cost washing machine. The workshop brought out some very interesting and fascinating ‘ways of seeing’ that completely overturned the engineering/tech/product way of approaching design problems. Did we need to redesign the washing machine (product) under stricter constraints, like the way most people think—start with an existing product, strip it of features, use cheaper materials and processes, reduce quality and make it low-cost. Or did we need to go up a level and reframe the problem itself?”

The answer, he says, lies in the context, which is about culture, geography, climate, behaviour, resources and energy within the boundaries of environmental friendliness and ecology. Everything else is secondary—design, materials, processes, technology and, finally, economic considerations.

When we think of the BoP, we generally tend to put economics first, but according to Malhotra, this is wrong. “I have deliberately kept economics at the bottom of the list. Call it ‘inversion thinking.’ Economics drives everything in today’s world, whereas it is merely a function of supply and demand. In my view, the concept of low cost itself is deeply flawed. What we should really concern ourselves with is lower price and, however counterintuitive it may seem, lower price is not simply lower cost. I’m no economist, but my business sense tells me that I can drive the price down by increasing volumes and reducing profits. Besides, adopting newer business models such as crowd-sourcing and collaborative manufacturing can help address this key issue. So, we must all remember that low cost is different from cost-effective, which is different from value-added. Unless the envisaged product enhances value, low cost has no meaning,” he says.

From the technology standpoint, Srinivas feels the same. He says, “A low-cost product is a misnomer in my opinion. It is a product for the low-cost segment of the market but it need not be a low-quality product. Products in these segments need to be designed ground-up for success. There is no way an existing product replaced with lower-cost components can be a success here.”

That said, he points out that electronic component costs have also gone down significantly in the recent past. “The mass-volume products drive down the cost of these components. Interestingly, OEMs in other industries now tend to use products or components from the PC and mobile industry to drive costs down. Processor costs for a single-core Cortex A8 at 1 GHz have gone down to as low as $6 this year, while two years back these commanded a healthy premium of $20. Memory costs have also been driven down, though they fluctuate due to the changes in supply and demand. The other major component for which costs went down significantly is the display. However, for applications that need strict qualification, like in the military and automotive domain, the price erosion has been far lower.”

Dorai Thodla, founder of iMorph Inc., gives us his take: “There are two ways to build a product for this market—innovation in low-cost methods, or high volume of sales with normal methods.” So, you need to consider both schemes to balance value and cost for this market.

How about something like…

If you wish to get into making or selling tech to the masses, look to these interesting examples suggested by our experts for motivation.

Inspiring DIY stories. “There is something called the Maker Movement in the US. It is a self-help culture of building things you need. People who are involved or touched by the Maker Movement build simple prototypes and turn them into low-volume products (initially). Many of them involve electronics. Of late, I have been hearing of many Indian examples too,” remarks Thodla. For example, a student created an app that couples a moisture sensor with an Arduino, which tweets when the moisture content is below a certain level (he wanted to connect this to a drip irrigation system). A lot of innovative products are being powered by Arduino (and its variants), Raspberry Pi and others. Plus, a variety of sensors attached to mobile devices are serving as low-cost diagnostic and healthcare tools. Solar lamps, cookers and the like are also becoming popular themes, for both start-ups and independent innovators. “Though expensive initially, these will eventually lower running costs (due to the reduction in oil and electricity usage) and make sense for the BoP. The next generation of these devices will be enabled by intelligence (such as lamps that turn on/off based on ambient light),” says Thodla.

MACi ECG machine. “GE India has been a pioneer in reverse innovation, leading product design for emerging markets. Its innovations are not just a cost reduction of existing designs, but completely redesigned from the ground-up to make a product that is several times cheaper and yet offers reasonable value,” says Srinivas. GE’s low-cost MACi ECG machine, launched a few years ago, was developed by researchers in Bengaluru after understanding the need for a low-cost, durable, portable ECG machine for low-income communities. MACi is battery-operated, portable and capable of printing in three channels. With one battery charge, it can complete 500 three-channel ECGs or 250 single-channel ECGs. So, with one battery charge, it can be used in a rural hospital without electricity for close to a month. MACi is priced at around Rs 25,000 and can be bought through easy monthly instalments. After successful early adoption, the machine was also adapted for sale to value-oriented customers in developed nations like the US.

Lullaby Baby Warmer. Another of GE’s low-cost, high-value innovations, Lullaby Baby Warmer provides 69 per cent warm-up, enabling nurses to handle new-born arrivals with much less stress. The product offers value for money and ease of use, both of which are essential for mass usage. GE has incorporated technology in the form of the Calrod heater for uniform heat distribution, which makes it easy even for novices to place the baby in the warmer. The warmer also has colour-coded safety alarms, a visually-coded control panel and well-positioned lights for easy usage. According to the company’s reports, the instrument offers cost savings of up to ` 107,000. It consumes 60 per cent less power on start-up and 20 per cent less power over 24 hours. There are more cost savings due to Calrod’s lifetime warranty, lower wattage and reliable probes. “GE’s MACi ECG machine and the Lullaby Baby Warmers have won international acclaim. Now these products are exported to several countries including developed nations,” says Srinivas.

Mobile-controlled irrigation. Nano Ganesh is an application developed by Pune-based Ossian Agro Automation. It has been in use for around five years now, and continues to be popular in Maharashtra. It has even been recognised by the World Bank as a notable technology for developing nations, due to its simplicity and affordability. Nano Ganesh, which also won a Nokia innovation award, allows farmers to turn their irrigation pumps on and off by remotely using a mobile phone. A mobile modem is placed on the pump and connected to a basic mobile phone. This allows remote control of the pump’s starter panel. When the farmer calls this phone from any location, a tone is heard if the motor is on, and there is no sound if the motor is off. The farmer can then turn the motor on or off through a 440-volt starter switch that responds to a code number sent via SMS from the farmer’s mobile phone to the phone attached to the motor. Nano Ganesh can be attached to any electrical starter and motor pump. It costs Rs 2800 plus taxes, and setting it up is easy and automatic. Users do not have to be literate to understand the simple tones. Overall, it makes sense for the agro community.

Low-cost smartphones. The initial smartphones arrived at a price-point of ` 30,000, which was way too much for an average Indian. So, how best can this product be optimised for a low-income group? “The high-end phones came with support for multi-band 3G roaming capability. For an average Indian, this is not needed. So, costs are saved by removing this feature. Optimising the software for lower memory footprint gives the opportunity to save some more costs. Earlier, systems used NAND flash boot while still having an SD card. Products for the low-end markets pushed technology to use an SD card boot, thus saving the cost of additional memory. While a natural drop in the prices helped this market, lower-resolution displays and using a single speaker to give virtualisation effects all helped address the needs of this market. Adding dual-SIM capability added the icing on the cake for this segment,” explains Srinivas beautifully!

Tata Nano. This is a moderately successful car, with decent value and low cost. “The car is designed for those who can afford a two-wheeler but can stretch a bit to get the comfort of a car,” says Srinivas. “This meant the car had to have all the necessary features but be priced effectively. This implied optimising the space inside the car, which also meant re-positioning the engine accordingly, for both efficiency and space. This needed a complete re-design of the engine and chassis. Tata Motors also went ahead and re-designed the doors and windows for lower weight so as to improve the efficiency. Components have been manufactured indigenously to the extent possible to save on the import costs.”

Cost-effective computing. In 2011, the government of Rajasthan focussed its attention on a massive computer education program, which involved setting up computing labs in around 2000 schools spread across the state’s 33 districts. If implemented the traditional way, it would have meant an unbearable initial investment atop the ongoing costs in support, maintenance, power supply and so on. Exploring alternatives to this, they came across NComputing’s practical and cost-effective computing solution. NComputing offers desktop virtualisation solutions, which give access to computing at a fraction of the cost of traditional server-PC based networks. This enables educational institutions, hospitals and rural BPOs to realise their dreams at lower price points. Typically, an average computer user uses merely 5-10 per cent of the PC’s capacity; the rest (approx. 90 per cent) goes waste. In the case of the Rajasthan schools too, their choice of NComputing solution was based on the logic that school children use just a fraction of an average PC’s computing capacity, since their learning needs are quite simple. Setting up individual PCs for each student is therefore a waste of capacity and money. Hence, they set up 10 NComputing virtual desktops in each lab, which utilise the unused computing power of the PC and share with multiple users using NComputing’s vSpace desktop virtualisation software. A keyboard, mouse and monitor are connected to each NComputing access device, making it appear as if each student has a PC to work on! Apart from the low hardware acquisition cost, the solution also meant 75 per cent less support and maintenance costs, and 90 per cent less energy consumption as NComputing devices use just 1-5 watts of electricity compared to 120-150 watts in a traditional PC. This is a critical advantage in remote parts of the state where power supply is a perennial issue. In many ways, including cost, NComputing’s solution seemed a best fit for rural India’s computing needs.

Cost-effective computing

There are lots more opportunities and even more ideas, if only we pause to think about the needs and income levels of the masses. According to a Press Trust of India release dated February 2013, after the unfortunate women harassment incidents in New Delhi, Union Minister of Communications & IT, Kapil Sibal, said to Rajat Moona, director general, C-DAC, “I want a wrist watch that will videograph, set up an alarm and will call up dedicated lines. Let’s have a GPS system, and let’s produce this watch for less than ` 1000 for the safety of the citizens of our country.” Let us hope to see this and other ideas come to life, soon!

The author is a technically-qualified freelance writer, editor and hands-on mom based in Chennai