JUNE 2012: A standard TV set displays images and video in two dimensions (2D). It lacks the depth that forms the third dimension of viewing.

In real life, when you view an object, either eye sees a slightly different picture from the other due to a minute variation in the angle. The difference between the views of both eyes is greatest for objects closeup and tapers off for those farther away. Using that information your brain calculates the distance between you and the object, helping you perceive depth and see in three dimensions or 3D.

To create a sense of depth on the screen in 3D, videos are shot from two slightly different angles corresponding to the average distance between human eyes. In animated films, these ‘shots’ come from computer models that generate the two views. In live action, two cameras are used to record stereo video.

At the movie theatre: polarisation

Previously, the 3D effect was created by using colour to separate the image intended for either eye. It utilised the anaglyph method of encoding a 3D image in a single picture by superimposing a pair of pictures.

Current technology utilises a property of light known as ‘polarisation.’ In a cinema hall, the 3D projector uses polarised filters to project two images—a right-eye perspective displayed with clockwise-polarised light and a left-eye perspective with counterclockwise light. The audience wears special polarised glasses that allow only the right-polarity light to enter each eye. The brain receives the two different perspectives with different polarisations and assembles these to create an image that has depth.

If polarisation is linear, the audience have to sit with their faces aligned to the screen. But if circular polarisation is used, the audience are free to sit in a more comfortable position.

At home: active and passive 3D

Active 3D. 3D-enabled LCD or plasma TV sets work quite differently from the technology used in cinema halls. TV-based 3D technology rapidly flashes alternating left-eye and right-eye video frames. The glasses worn by the viewer are also not polarised but active shutter glasses.

As a right-eye video frame flashes on the screen, the LCD over the right eye switches from opaque to transparent state. When the left-eye video frame appears, the right-eye LCD turns opaque again and the left-eye LCD becomes transparent. At any moment, you see only one perspective, through one eye. But the left and right video images alternate so quickly—at 120 hertz (times per second)—that you perceive a full 3D view. This illusion is possible due to persistence of vision.

What is not so great about this technology is that you have to wear glasses.

Passive 3D. Here the TV divides left- and right-eye perspectives into alternating vertical columns. Microscopic lenses over the screen ‘bend’ the light so that slices of the right-side perspective reach the viewer’s right eye and slices of the left-side perspective reach his left eye.

The benefit of this technology is that it does not require the viewer to sit directly in front of the screen. New TV screens use several sets of lenses to create multiple left and right image pairs for viewers sitting at different angles from the TV. One set of images is for viewers seated directly in front of the screen. Another is for viewers to the side of the screen. Additional pairs take care of all the viewers in between. If you move sideways, you simply transition from one pair of right-left images to the next.

This technology does not require you to wear glasses but the 3D experience is nowhere close to that of active 3D technology.

In smartphones: autostereoscopy

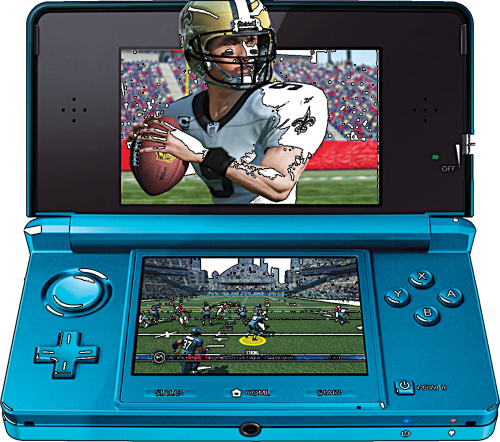

Autostereoscopy is the process of displaying 3D images or stereo images without using specialised headgear. It is also known as glasses-free 3D and is the major technology used in 3D smartphones such as HTC EVO 3D and LG Optimus 3D, and portable gaming devices such as the Nintendo 3DS.

This technology uses the principle of parallax barrier to deliver different images to each eye. The latest and most convenient design does not have the physical parallax barrier in front of the pixels, but behind the pixels and in front of the backlight. Thus it doesn’t send different images but different light to the two eyes. This allows the two channels of light to pass through the pixels, allowing glare over the opposite pixels, giving the best image quality.

What’s next?

A different TV programme for everyone. 3D technology is being tested for use in such a way that we can build devices that show different images or videos to different people looking at the same screen. Currently, 3D devices send different images to the two eyes. With a fair amount of tweaking, it can also be possible that these devices send different images to different pairs of eyes. For instance, in passive 3D TV, the angle at which the viewer sits away from the TV set decides the pair of right-left images he sees. If different pairs of right-left images carry different programmes, we have the ultimate solution to the age-old family problem of fighting over the remote control.