While the move to smaller transistors has been a boon for performance it has dramatically increased the cost to fabricate chips using those smaller transistors. This forces the vast majority of chip design companies to trust a third party, often overseas manufacturers, to fabricate their design.

To guard against shipping chips with errors (intentional or otherwise) chip design companies rely on post-fabrication testing. Unfortunately, this type of testing leaves the door open to malicious modifications.

The paper from research team from University of Michigan won “best paper” award at IEEE Symposium on Privacy and Security, last month. With a proof-of-concept, they detailed the creation of an insidious, microscopic hardware backdoor.

By a series of seemingly innocuous commands on their minutely sabotaged processor, a hacker could trigger a feature of the chip to access the operating system. More dangerous is the fact that, this microscopic hardware backdoor can’t be caught by the current methods of hardware security analysis. This makes it entirely untraceable and could very easily be planted by an employee in the chip factory.

Since attackers craft attack triggers requiring a sequence of unlikely events, these are never encountered by even the most diligent tester, and you thought adding a complex password was enough.

“Hardware is the base of a system. All software executes on top of a processor. That software must trust that the hardware faithfully implements the specification. For many types of hardware flaws, software has no way to check if something went wrong.”

This in mind, a team of researchers from the research team from University of Michigan set out to check if it could be turned into a security threat. The results were astonishingly true.

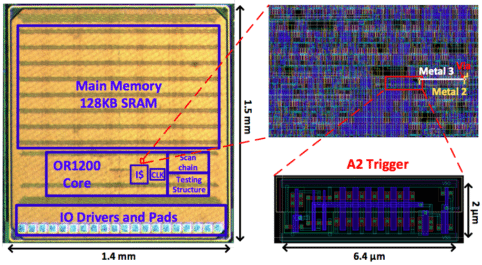

In the open spaces of an already placed and routed design, the research team constructed a circuit that used capacitors to siphon charge from nearby wires as they transition between digital values.

When the capacitors fully charge, they deploy an attack that forces a victim flip-flop to a desired value. The team then weaponised this attack into a remotely-controllable privilege escalation by attaching the capacitor to a wire controllable and by selecting a victim flip-flop that holds the privilege bit for our processor.

The entire attack was implemented on an OR1200 processor and a fabricated chip. Experimental results showed the attacks to be working. The attacks elude activation by a diverse set of benchmarks, and suggest that attacks evade known defenses.

The back-door into the system, is being dubbed as “demonically clever” by some industry veterans, and rightly so. After all it is a needle in a mountain-sized haystack.